On Opposite Sides of the Travel Ban

When a controversial executive order on immigration was implemented in January 2017, two YLS alumni reunited in the most unexpected way

Farshad Ghodoosi ’15 JSD, ’12 LLM was returning from a family vacation in Morocco with his wife on January 29, 2017, when Customs and Border Protection agents at JFK Airport detained him on his way off the flight.

Ghodoosi, a green card holder and permanent resident of the United States, knew he might encounter trouble after hearing about the hasty and chaotic rollout of a controversial ban on immigrants from several Muslim-majority countries. However, he had no idea what a nightmare the next several hours would become.

Separated from his wife, Ghodoosi was detained for four hours in a small back room, uncertain of what was happening and humiliated by not even being able to use the restroom without supervision.

Here they were, two Yale Law graduates who bonded in New Haven during a reading group on Islamic law and jurisprudence, now on opposite sides of the attorney-client experience simply because of one’s national origin and religion.

“My heart was beating, hoping that [the agent] would not send me to the ‘other room,’ but he did,” recalled Ghodoosi, an attorney for an international arbitration firm in Washington, D.C., who was born in Iran.

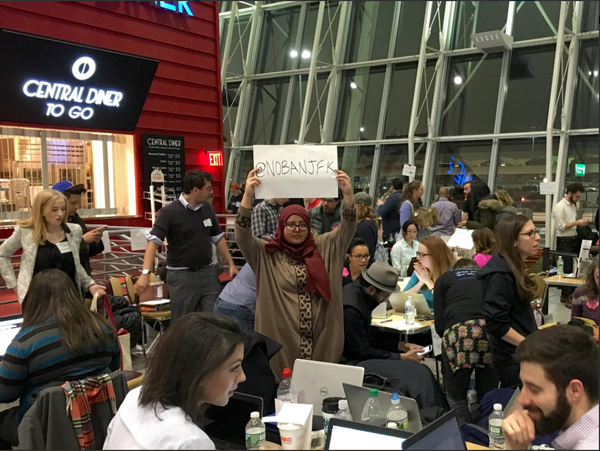

Outside, the country was processing the executive order issued by the Trump administration, which came with hardly any explanation or guidance for how it should be handled. Protests erupted around the country. Legal organizations — including the Worker & Immigrant Rights Advocacy Clinic at Yale Law School — worked around the clock to challenge the constitutionality of the ban. And an army of lawyers arrived at airports to help those like Ghodoosi, who were being unjustly detained.

Amanda Elbogen ’13, an attorney with Kirkland & Ellis LLP in New York, was one of those lawyers. As the granddaughter of four Holocaust survivors, Elbogen was particularly horrified by the discriminatory ban. She jumped at the chance to help.

“I got the email from my firm’s pro bono coordinator saying that help was urgently needed at JFK Airport,” said Elbogen. “I wrote back and asked her to let me know what I could do.”

When Elbogen arrived at JFK, she saw about a dozen lawyers hunched over laptops, furiously working on habeas petitions — petitions developed by WIRAC students and faculty who were leading the charge to fight the ban back in New Haven.

“I recognized a colleague of mine at the law firm, who was writing a habeas petition for someone detained,” recalled Elbogen. “Soon after I joined him, he got an email from someone at the firm saying that a partner had heard of a particular individual detained, whose wife was at the airport and could still communicate with him via text, and they were hoping someone could take that case and find her.”

“I looked at the name — Farshad Ghodoosi,” recalled Elbogen. “And I realized, this is someone I know — someone I was friends with in law school. It was a surreal moment.”

Here they were, two Yale Law graduates who bonded in New Haven during a reading group on Islamic law and jurisprudence, now on opposite sides of the attorney-client experience simply because of one’s national origin and religion.

“She was among the YLS students who cared about and respected other cultures and would approach them with intellectual curiosity, not biases,” said Ghodoosi.

Communicating via text, Ghodoosi was providing updates to his wife, Monica, who was now with Elbogen outside the gate. Elbogen began to interview Monica as she filled out Ghodoosi’s habeas petition, and offered advice over the phone. She also petitioned the Customs and Border Protection officers directly for his release.

“I spoke to CBP officials several times, telling them I was Farshad’s attorney and wanted access to see him, and informing them that he was a green card holder and that they were acting in violation of recent injunctions issued by the federal courts,” said Elbogen.

Outside of the airport, WIRAC had teamed up with other legal organizations and secured the first of several nationwide injunctions ordering the government not to remove, among others, any “individuals from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen legally authorized to enter the United States.”

But inside the interview room, Ghodoosi was still dealing with two agents who were grilling him on his trip.

“I remember the officer started with a serious tone asking questions about my trip, my family, and my connection to Iran,” said Ghodoosi, who was watching as the agent took extensive notes. Once the agent realized that Ghodoosi was educated at Yale and worked as a lawyer, his attitude quickly changed. “I remember in the process his tone became friendly,” recalled Ghodoosi. The agent then asked Ghodoosi how he felt about the ban.

“The experience will stay with me as a reminder of my obligations as a lawyer, citizen, and human being to stand up and fight injustice." —Amanda Elbogen '13

“I told him my opinion and he quickly confessed that they themselves didn’t believe it would be effective and they really didn’t know what they were doing,” said Ghodoosi.

From there, a rapport was established, and he was released. Ghodoosi later learned that on the same day, the White House decided the ban would not apply to green card holders.

“I quickly left the room and the area and reunited with my wife,” said Ghodoosi. “It was there where I saw Amanda. I was really happy that Amanda was there to help me and give courage to my wife during this process.”

“After Farshad was released, we felt a rush a relief,” said Elbogen. “I interviewed him to memorialize what had happened. I can’t claim any direct cause and effect in his release, but I am confident that the cumulative impact of all the lawyers assembled in JFK made a big difference in ensuring individuals were released, and sooner rather than later.”

It was an experience that up until that day would have seemed unimaginable in America. One year later, the executive order has prompted numerous successful legal challenges, several revised orders, and appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I never would have thought that the U.S. would undertake such an obviously discriminatory action,” said Ghodoosi, who had many friends and family members affected by the executive order.

“My Iranian friends’ parents have been prevented from seeing their children and grandchildren,” he added. “I could see the distress and anxiety in all of my Iranian friends—surprised by the ban and uncertain about the future. This still continues to this day and will continue.”

But looking back, there is also a hopeful lesson that has left an indelible mark on both young lawyers. Through the chaos, sadness, and distress, the experience demonstrated the true power of law and the role lawyers can play in protecting this nation’s core values when they are tested.

“There was the very dark side to the story,” said Ghodoosi. “But the bright side was the overwhelming support we received from lawyers and others during this process. It was truly inspiring.”

“The experience will stay with me as a reminder of my obligations as a lawyer, citizen, and human being to stand up and fight injustice,” said Elbogen. “It is ordinary people’s apathy and indifference that has allowed the world’s worst human rights abuses to take place, and it is heartening to know that U.S. citizens and the legal community are not going to stand by and let our democratic institutions and principles be weakened.”