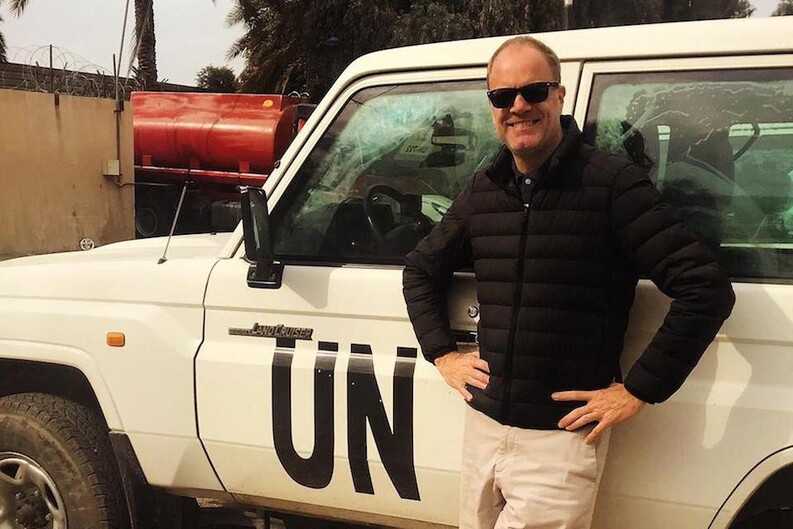

Schell Center Fellow Spotlight: David Marshall

David Marshall is a current Visiting Human Rights Fellow at the Schell Center for International Human Rights. Marshall has worked as a human rights lawyer with the U.N. for many years, including with the U.N. human rights offices in Sudan, Nepal, and Kosovo. In this interview, he speaks about his experiences with the U.N. and his goals for his time as a Visiting Fellow.

Q: Can you start by telling us a bit about your background with the U.N.? What major projects have you worked on and what roles have you taken on?

DM: I was hired by the U.N. in 2003 as the Criminal Procedure Advisor with the Human Rights Office, and I spent about 15 years working on criminal law reform issues in fragile states, criminal accountability for atrocity crimes, and investigations of human rights violations. In the past year I was with the U.N. human rights office in Baghdad, Iraq, where I led a team responsible for monitoring the investigation and prosecution of ISIL defendants charged under the Iraqi counterterrorism law for ISIL atrocities committed between 2014 and 2017.

Q: Could you speak more about the recent project monitoring ISIL defendants? What did that process entail, and what were the challenges of the project?

DM: In 2017, the U.N. Security Council passed a resolution which established an investigation team to assist Iraqi authorities in their investigation and prosecution of ISIL crimes. The terms of reference of the U.N. investigation team included a provision that stated they would only hand over evidence they had collected if there were assurances from national authorities that the legal process was fair and independent. So, I went from New York, where I had been working on human rights law and policy issues in the U.N. Human Rights Office, to Iraq to help the U.N. mission there monitor the ISIL cases. In a year, we monitored about 150 cases of the thousands of ISIL defendants who were charged and detained under the Iraq counterterrorism law.

Ensuring security for our team as it moved around the country posed a significant challenge. ISIL is still a major threat in much of Iraq, particularly in areas like Mosul where we were undertaking our observations.

Moreover, we had to build trust with local legal actors in order to gain access to the investigation files and investigation hearings. This in turn would allow us to draw firmer conclusions on the question of fairness and independence. We built up those relationships over a number of months, and the consequence was that, remarkably, we obtained access to investigation hearings of senior ISIL leaders including the head of ISIL’s intelligence arm, the head of ISIL’s curriculum development, and the head of ISIL in Anbar, a province in Iraq where there were a large number of atrocities against civilians.

The end result was a deeper understanding of the functioning of the Iraqi justice system, due process concerns emerging in these cases, and how allegations of torture of suspects were being addressed. Surprisingly, we also saw the increased use of forensic evidence in many of these cases. With those insights, our team would visit the Iraqi Chief Justice and other senior judges to share our observations and get feedback.

Q: Do you often find it difficult to work with domestic actors as a representative of the U.N.? How are those relationships built?

DM: It’s always a challenge coming in as an international expert — especially to a place where the international community has been providing “expertise” for more than a decade, often with modest success. So, a lot of the early part of forging relationships is just building trust and confidence, and that means that domestic actors need to see you as someone who has a body of expertise and knowledge that’s of value to them. I spent fifteen years as a trial lawyer before I came to the U.N., I did pro bono work for Amnesty International on criminal justice issues, and I have an understanding about how civil law systems function in fragile states. I think it’s important to national counterparts that they see that I have a technical understanding of the machinery of justice in their country.

Moreover, you have to come to this work with a sense of humility. I don’t speak Arabic. I don’t know the Iraqi justice system in any deep, meaningful way. Being aware of that is really key. It’s also key that you’re acting in good faith. We’re not seeking access only to produce a public report condemning the whole justice system — we’re actually trying to help by providing some useful insights. For example, torture, cruelty, and ill treatment are endemic in the justice system in Iraq. We could have named and shamed and publicly said that Iraq was violating international treaties that they ratified (which the U.N. presence in Iraq had been saying since 2006), but I came at it from a different angle. We thought about how we can help working-level staff in law enforcement interrogate suspects using a model that has proved successful with other law enforcement agencies, without recourse to torture. With this model, based on the UK PEACE interrogation initiative, law enforcement could ensure more reliable confessions and more confidence in the justice system.

The same approach goes for the death penalty. There is no U.N. policy on abolishing the death penalty. Yet previous U.N. human rights reports had publicly demanded that Iraq abolish the death penalty, all to no avail. I didn’t see the utility in persisting with that advocacy posture. I would rather focus our U.N. leverage, if we had any, on supporting alliances among government, the judiciary and the Bar Association on strengthening due process protections found in national and international law.

Q: You also led an investigation into human rights violations in South Sudan. What kinds of strategies and skills are necessary for those kinds of investigations?

DM: I was the team leader for the U.N. investigation into killings and atrocities in South Sudan in 2015 and 2016, and I thought the three-month job was “Mission Impossible.” I had to hit the ground running with a crazy to-do list: find safe office space and accommodation; discuss, agree and then launch the strategy for my team of investigators none of whom I chose, many of whom had never worked for the U.N. or in places of conflict; agree on an MOU with the government on access to people, places and documents; and address the mundane - how to follow U.N. rules and regulations when spending $100,000 in cash, which means I needed written receipts for everything, in a country in conflict.

To do the job, you need legal skills, you need a strong understanding of both international humanitarian law and international human rights law, and you need to understand the local legal framework and practice, because if you’re talking about human rights violations they could be at the national level and international level. You need political skills to deal with the diplomatic community and with the U.N.’s many moving parts in country, some of whom are not particularly happy you are there “causing problems with the government.”

And then you need to know how to manage your team and handle the unexpected on a daily basis. The legal advisor that we hired didn’t have an international humanitarian law background and came down with malaria and had to leave, so I had to take over, which is not what I had anticipated. Late in our three months we were told that the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights wanted the investigation to only focus on the culture of violence generally and the nature of the relationship between the two warring parties’ leaders but not on current violations — so not an investigation as requested from the U.N. Human Rights Council but an historical document, which was not something we were hired to do.

Q: You have worked in a number of countries around the world. How has this varied experience shaped your perspective on human rights broadly?

DM: There is an accountability crisis within the U.N. human rights machinery, which has many moving parts — the U.N. Human Rights Council, the U.N. Security Council, to name just two. The international system seems stuck in a cul-de-sac of fact-finding from Myanmar to Syria, Libya to South Sudan. The “accountability movement” needs to stop grinding its wheels over the gathering of facts simply for the sake of gathering facts, and re-think what accountability for international crimes could meaningfully look like.

Two weeks ago, I was interviewed by the current U.N. investigation team into human rights violations in South Sudan. Some three years after my team presented its report to the U.N. Human Rights Council concluding that the government was the main perpetrator of atrocity crimes and sexual violence, the Council was again considering to focus on fact-finding. How useful is a new fact-finding mandate to victims and survivors and their families? It will just further undermine confidence that the international system is capable of preventing and punishing international crimes.

Two new developments are worthy of examining further – the recently established U.N. mechanisms for Syria (created by the U.N. General Assembly) and Iraq (created by the U.N. Security Council), focused on, in essence, the gathering of evidence and preparation of files for investigation and prosecution. It’s early days for both, but perhaps this is the direction the U.N. needs to go — more modesty and more dedicated technical expertise, with a lowering of noisy rhetoric about accountability.

Q: What do you hope to do with your time as Visiting Human Rights Fellow at the Schell Center?

DM: I just finished my fifteen years at the U.N., and I really need to decompress. I want to write about this accountability conundrum — whether in addition to the new mechanisms mentioned, there’s something else the U.N. should be thinking about. I also want to explore some topics around Iraq itself and put together a research project around litigating the counterterrorism law in Iraq. There’s no legal culture in the Middle East generally around “facial challenges” to statutes, and the counterterrorism law for which ISIL defendants are prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to death is, I believe, deeply flawed. Working with a lawyer in Iraq and others, I’d like to support a constitutional challenge to the law.

Also, no one really has explored the impact human rights investigative work has on the human rights staff themselves, particularly those working in environments like South Sudan or Iraq. Nothing prepares you for interviewing a child victim of gang rape or someone who was the survivor of an atrocity that occurred in a police station in December 2014. The U.N. provides no training or other forms of support for such staff and cares more that staff follow U.N. rules and regulations than about their staff’s health and welfare. This needs to change.

Finally, I want to share with people at the law school and at the University more broadly what life could be like in the U.N., to give a sense of where that path could go if you wish to work at an international organization, from whichever perspective — legal, political or human rights.