Agnieszka Fryszman Discusses Taking on Big Corporations

On February 26, the Schell Center hosted a talk with Agnieszka Fryszman, whose private international human rights practice at the law firm Cohen Milstein is considered one of the best in the world.

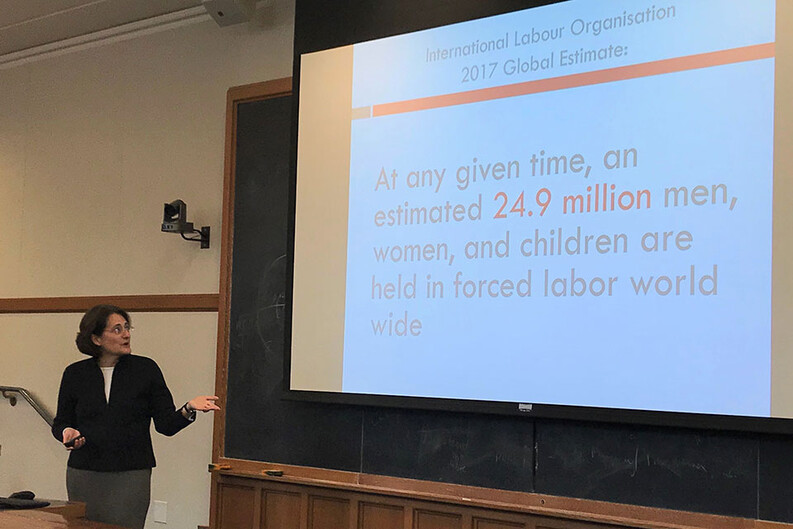

Recently, Fryszman has focused on human trafficking litigation. “Trafficking is affecting more and more people thanks to the transnational nature of the global economy,” she said, “and we’re at a point where it’s hard to get jurisdiction over a foreign corporation that has trafficked people abroad.”

As Fryszman explained, most victims of human trafficking are recruited from places of extreme poverty, forced to pay recruitment fees to a labor broker, then taken to an unfamiliar country where they are sent to work in factories, on ships, or elsewhere – mostly in facilities that sell products to foreign suppliers. “It’s a huge challenge to stop this,” said Fryszman. “Trafficking is super profitable – people are viewed as a renewable resource, in that it’s cheaper to traffic their replacements than pay them.”

Fryszman is no stranger to holding enormous corporations accountable for human rights violations. Her past clients have included Holocaust survivors suing Swiss banks for collaborating with the Nazi regime during World War II, and survivors of Nazi-era forced labor camps taking on the German and Austrian companies that allegedly profited from their slave labor.

Human trafficking litigation, however, presents unique challenges, such as determining what level of corporate involvement in trafficking operations is criminal – for instance, does profiting off trafficking make corporations liable? Fryszman argues that being linked to trafficking in any way should make corporations culpable. “If there’s no liability at the top of the chain, there’s really not going to be any accountability farther down,” she said. “We have to target the people who have the political and economic power to make [trafficking] stop.”

In two recent human trafficking cases, Fryszman has aimed to hold American corporations accountable in U.S. jurisdictions for trafficking committed abroad. Fryszman successfully defended two Indonesian men who were trafficked onto a fishing boat run by an American captain in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The men were forced to work 20-hour days, denied medical care, paid half of what they were promised, and abused by the captain, who threatened to fine them thousands of dollars if they left before their contract ended. They managed to escape their boat when it docked in San Francisco. Fryszman took the men on as clients and argued in court that they were victims of chattel slavery. She won the case, and the resulting settlement dictated that the captain had to give workers Know Your Rights flyers and employment contracts written in their own language.

Fryszman and her legal team had less success when they represented two Cambodian men who were trafficked4 to a seafood factory in Thailand that exports to the U.S. There, the workers received meager wages and endured conditions so deplorable that, Fryszman remarked, “their experience was almost like sharecropping.” In June 2016, Fryszman and her colleagues filed a complaint in a California federal court, accusing the U.S.-based companies who bought products from the factory for violating the Trafficking Victims Protection Act. But the judge ruled against them. The legal result was devastating to their clients, who are unable to find work to pay off their debts and fear retribution from their traffickers. One of the men is unable to afford medicine for his children; the other had to sell his farmlands to pay his debts.

These cases taught Fryszman about the risks trafficking victims take in speaking out and the importance of working with local NGOs and community members. “Clients might not come to the American legal process with the sense that they have rights, and they may not be used to speaking up for themselves.” She added, “We had to prepare our clients a lot so that they would not defer to authority, so that they would only answer the question they were asked.”

Fryszman stressed that, in order to make progress, “we have to build capacity in the places where we’re working – people should know how to gather evidence, write an affidavit, and so on.” She added, “We won’t succeed unless people have the capacity to address [trafficking] in their home countries, not just in international bodies.”