Alfred Brownell on a Career Protecting Environmental Rights in West Africa

Alfred Brownell began his Nov. 10, 2021 talk by describing the land where he was raised. Robertsport, Grand Cape Mount, in the Republic of Liberia, neighbors both mountains and Lake Piso, the country’s largest lake. The Atlantic Ocean almost totally encircles the town. Growing up there with his single mother, Brownell recalled that he would venture twice a week into the mountains to find firewood, harvesting “goodies” such as monkey apples and forest bananas along the way. And he recalled getting into fights with his childhood friends for releasing migratory birds caught in snares the other boys set up on the beach.

“I never thought I was protecting the environment when I loved the ocean, protected the migratory birds, or when I got the dead wood to cook, never cutting [living trees],” Brownell said. “You are not aware as a kid that a lot of the things you do come back to influence you and your behavior in the future.”

Today, Brownell is an internationally recognized environmental rights activist and lawyer. Living in exile from his home country of Liberia, Brownell is currently the Tom & Andi Bernstein Visiting Human Rights Fellow at the Law School’s Schell Center for International Human Rights.

In Liberia, he co-founded and headed Green Advocates International (GAI) and collaborated with activists in several West African countries to co-found one of West Africa’s largest solidarity movements — the Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform (MRU CSO Platform). He also founded West Africa’s first public interest lawyers’ network, the Public Interest Lawyering Initiative for West Africa (PILIWA). In 2019, Brownell won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, considered the “green Nobel,” which honors the achievements and leadership of grassroots environmental activists globally.

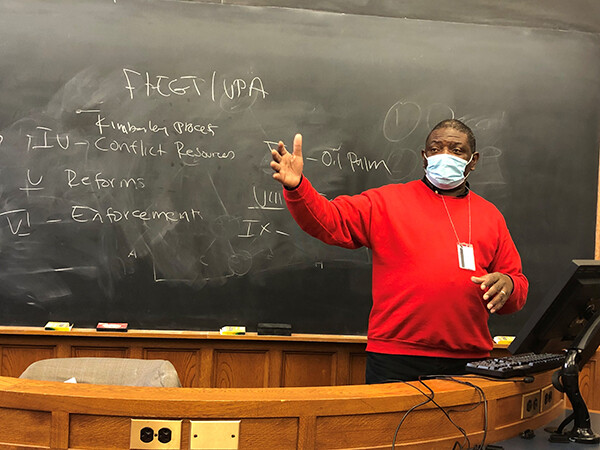

At his talk, “Environmental and Human Rights Protection in West Africa,” Brownell gave an overview of his work supporting environmental and human rights in Liberia, West Africa, and beyond.

Using a Legal Education to Lift Up the Marginalized

Brownell explained that he became a lawyer essentially by chance. He originally wanted to become a medical doctor, he said, but his poverty made that dream impossible. Instead, he accepted a scholarship to study agriculture; unable to find employment after graduation, Brownell started a small piggery farm.

When Brownell decided to leave pig farming to go back to school, Liberia was in the midst of a brutal civil war, and many academic programs were closed. Law school was his only option. Brownell recalled how his law school classmates bullied him for his background, telling him that law school was no place for a pig farmer. His anger at their words energized him, he said, and he pursued his legal education with passion and rigor.

As he dedicated himself to his legal studies, Brownell began to form a deeper understanding of how the then-president of Liberia, Charles Taylor, was consolidating power by passing laws ensuring his control over Liberia’s natural resources. Laws such as the Strategic Commodity Act, the 2002 Minerals and Mining Laws, and the Forestry Laws upset him.

“I looked at the constitution and reviewed these laws, and I looked at what was happening in the country at the time, and I said, this is not right,” Brownell said.

His law school experience was formative. “My personal life today and the need to stand up and advocate for the poor, vulnerable, and marginalized was formed at the law school. That was when I started to get angry,” Brownell said. “The law school offered me tools and a legal education that I could use to ensure rights and justice for the poor and voiceless and to lift up people who were struggling.”

Lawyering with a Wide-Open Mind

After leaving law school, Brownell pursued this mission by founding Green Advocates International. Brownell and GAI investigated how the Liberian government was using the country’s natural resources, such as minerals and timber, to fuel the civil war. Along with other international organizations, they coined the terms “blood diamond,” “logs of war,” and “conflict timber.” At the time, Brownell said, “There were no laws or regulatory regimes to hold actors involved in these sectors accountable for the atrocities they committed. Our options were very limited on what we could do.” Changing how resources were used “seemed practically impossible,” he said.

In situations like these, Brownell reflected, younger lawyers and law students can become paralyzed by obstacles and challenges. “Sometimes my students say, we don’t have the tools, we don’t have the laws, we don’t have the information. How are we going to ensure enforcement?” he said. “As lawyers, we have to keep our minds wide open. We need to consider all the options.”

“Laws are only as good as their enforcement and implementation.”

—Alfred Brownell

'For example, Brownell said, “It is our duty to enable the promulgation of laws either through legislative, judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative processes, even if, in the medium term, they are non-legally binding or are ‘soft laws.’ Soft laws may eventually become hard laws. Dissenting opinions sometimes become case law.”

In fact, Brownell said, by targeting consumers and international bodies, GAI and other organizations were able to achieve significant global natural resources policy and institutional reforms. New trade regulations required that diamonds be legally certified as conflict-free and that timber be from a legal source.

As a result of GAI’s work, the United Nations Security Council also imposed sanctions on Liberia and mandated reforms of the country’s forestry and natural resource sectors. Brownell himself was involved in drafting the reformed forestry laws. “Laws are only as good as their enforcement and implementation,” he said. Even with the new, progressive laws in Liberia, Brownell said that the government sought loopholes to continue exploiting resources. They found one in the agricultural sector: land concessions. According to Brownell, the Liberian government has given away millions and millions of acres of forested land to corporations as “concessions.” Both the government and the corporations, he said, ignore Indigenous communities that already live on the land granted to the corporations.

“For centuries they have lived on the land,” he said, only to be displaced for companies’ profits. Concessions from the government have also caused extreme environmental damage, according to Brownell, as acres of forested land are cut to process wood into timber or to grow massive quantities of a single crop.

Building a Movement

To resist concessions, GAI built a grassroots network across Liberia by organizing rural and Indigenous communities. “We built a formidable movement,” Brownell said. “We organized and organized.” The resistance grew so strong that the 300,000 hectares of land given to one palm oil company as concessions was reduced to 10,500, because active Indigenous resistance meant that the corporations were unable to take over the land.

The success motivated Brownell and GAI to expand further. “Even if we protect the communities in Liberia, if we protect the environment in Liberia…we have to move forward,” he said. The movement has since expanded to Sierra Leone, Guinea, Côte D’Ivoire, Ghana, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria under the umbrella of the MRU CSO Platform.

In 2016, Brownell and colleagues in West Africa co-founded the Public Interest Lawyering Initiative for West Africa (PILIWA), identifying young lawyers and law students across West Africa and training them to provide support to this network of activists across the region. PILIWA covered more than seven countries and has brought cases before domestic courts, regional courts and before nonjudicial grievance mechanisms.

However, as the movement’s power increased, so did the risk. Brownell had received threats before, but as companies and governments saw that, as he put it, “we were not backing down, and we were winning,” the threats became more serious. In Liberia, for example, the government described Brownell’s advocacy to prevent deforestation and indigenous land-grabbing as seditious, threatened to revoked his license to practice law, and called his organization GAI a “super-state structure undermining the sovereignty of the country.” He and his family were forced to flee Liberia and come to the United States. Others from across the globe, he said, have not been lucky enough to escape.

Defending the Defenders

“Forces are marshalling against the planet, against the people,” Brownell stressed. “Thousands and thousands of Indigenous people and frontline environmental and human rights defenders, those who are saving the planet, are being slaughtered every year with impunity.”

Brownell asked the audience, “How is it possible that those who have put their lives on the line to protect people and the planet, our first responders and firewall, are being murdered — four persons every week — while we remain silent?”

He called on the future lawyers in the audience to support the frontline defenders — but, in doing so, to always remember who leads the movement. “If we don’t put them at the forefront of this process, then who are we representing?” he asked. “All we are doing is providing services to them. We are not the ones whose land has been taken, whose water has been polluted, who are being killed.”

The work is urgent now more than ever, Brownell emphasized. “The climate crisis is here. It is not going anywhere,” he said. “We need to figure out how to respond to that. The train has left the station.”