Author of Thalidomide History Tells Drug’s Hidden Story

In the 1950s and 60s, a new sedative called thalidomide was widely prescribed in Europe for nausea during pregnancy despite scant research on the drug’s impact on fetal development. The results are now well known: thousands of babies were born with truncated limbs or other severe injuries. Far less known is the story of thalidomide in the United States, however.

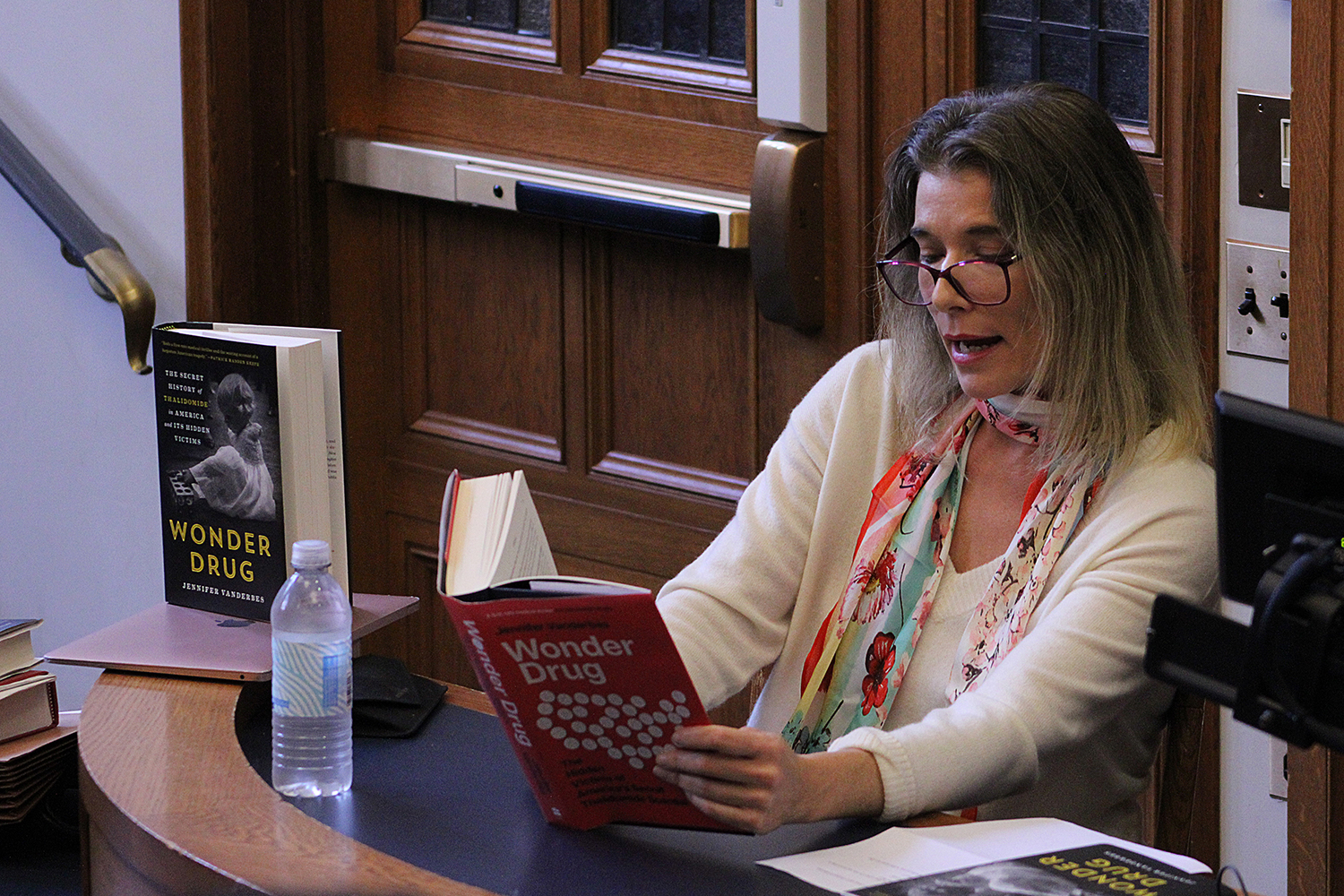

On Oct. 25, the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy welcomed author Jennifer Vanderbes to Yale Law School to discuss her book on this lesser known story. In Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and its Hidden Victims Vanderbes recounts how thalidomide was given to pregnant patients across the United States. Starting in 1959, an American pharmaceutical company quietly began distributing samples of the drug. U.S. doctors, who thought that thalidomide would soon have Food and Drug Administration approval, began handing it out freely under the guise of clinical trials. Even though the FDA would eventually block the sale of thalidomide, it still reached tens of thousands of unknowing patients.

Vanderbes began by sharing the story of a couple, Anne and Doug, from the book’s prologue. Their child, Carolyn Jean, was born with severe injuries caused by thalidomide. Anne was asked by her doctor whether she had taken any pills purchased in Canada during her pregnancy. But the doctor did not otherwise mention thalidomide, even though the drug’s risks were known in the American medical community. Anne and Doug were provided no support for their child, who was expected to die as an infant. Carolyn Jean, however, grew into a thriving adult.

Taking questions from Randi Epstein, Writer in Residence at the Program for Humanities in Medicine, Vanderbes discussed how the thalidomide story could have happened. Norms governing the doctor-patient relationship in the early 1960s and expectations for women’s behavior helped fuel the tragedy, she said.

Vanderbes highlighted the pivotal role of FDA medical reviewer Dr. Frances Kelsey in containing the drug’s reach. Kelsey halted the approval process for thalidomide despite intense pressure from FDA colleagues and thalidomide’s manufacturer. Kelsey was unaware of the pre-approval distribution of thalidomide under the guise of clinical trials until the drug had already made its way to patients. She was nevertheless instrumental in preventing thalidomide from getting to more Americans, Vanderbes said.

The “clinical trials” that took place without FDA approval were really a marketing scheme with few safeguards or reporting requirements for participating medical professionals, according to Vanderbes. Some physicians passed along the drug to colleagues and some hospitals stocked it in their pharmacies. Because informed consent was not yet considered a foundational part of the doctor-patient relationship, Vanderbes explained, patients were often given thalidomide in an envelope and told only that the pills were a vitamin. Despite patients not being told what drug they were being given, Vanderbes noted, someone who gave birth to a child with a thalidomide injury would still often be framed as recklessly taking an unknown drug.

Vanderbes concluded the talk by saying that the thalidomide tragedy, though not a direct analogue to more recent public health crises, may yet hold lessons for the pharmaceutical industry and government regulators. She also emphasized the work of thalidomide survivors, in the United States and around the world, to hold manufacturers and distributors accountable.