Decades-Long Friendship Sustains Litigators

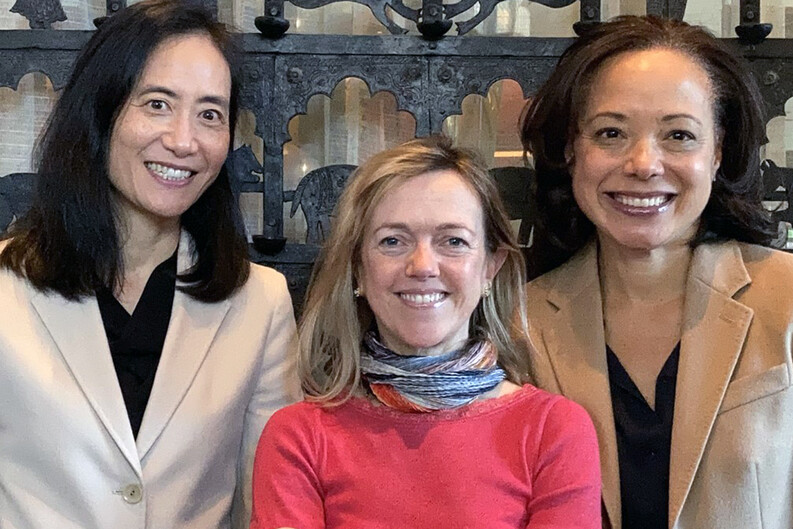

In 1995, two recent Yale Law School graduates — Joanna C. Hendon ’91 and Mei Lin Kwan-Gett ’92 — took jobs at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York. Within a few years, they were joined by a third, Dani R. James ’95. The storied federal prosecutor’s office in Manhattan — famous for its independence, tenacity, and jurisdiction that includes Wall Street — became a career launching pad for the three. And, as they pored over cases together, it was where their personal and professional relationships would flourish.

Since those early days, Hendon, James, and Kwan-Gett have become top litigators, each following sometimes overlapping paths through white-collar criminal defense and private law. Their careers and lives have had twists and turns, but the bond formed among the three women in those early years has been a source of support throughout.

Despite not knowing each other during law school, Kwan-Gett, now Deputy General Counsel and Global Head of Litigation and Regulatory Investigations at Citigroup, said the three felt an immediate sense of kinship when they began working together.

“I find that every job change requires a leap of faith to some extent. It’s so much easier to take that leap when a friend has made a similar move — and you can see them thriving.”

—Mei Lin Kwan-Gett ’92

“When you have an opportunity to work with another YLS alum, you often feel an instant connection, which, of course, makes it that much easier to forge a deeper bond,” she said. “And those deeper connections — others who can be sounding boards, advisers, support systems, and true friends — make such a difference in one’s career.”

Hendon, now Partner at Alston & Bird and co-leader of its White Collar, Government & Internal Investigations team, recalled that the Office of the Southern District of New York was largely male when she started, at least among the assistant U.S. attorneys. But she also remembered many female fellow assistant U.S. attorneys, including Kwan-Gett and Nancy Kestenbaum ’90, who stood out as role models and friends.

“Having both of them — both so incredibly bright, skilled and ambitious — as peers was important,” Hendon said. “They’re both so extraordinary.”

Hendon and Kwan-Gett became even closer after they were simultaneously promoted to the Securities and Commodities Task Force, then and now seen as an elite, sought-after unit in the office, according to Hendon. Kwan-Gett remembers many late nights in dreary conference rooms, parsing ideas for investigative steps and witness examinations over takeout.

“Joanna and I both joined the Securities Unit at a time when they were really ramping up their prosecution of boiler rooms (the type of pump-and-dump brokerage houses depicted in the movie The Wolf of Wall Street),” Kwan-Gett recalled, “and there are lots of memories from those days — reviewing trade blotters, listening to wiretap recordings, labeling evidence obtained from search warrants, and interviewing victims.”

Hendon and Kwan-Gett were established in their roles at the Southern District when James, who is now a Partner and Co-Chair of White Collar Defense and Investigations at Kramer Levin, joined them. James had spent her first years out of law school working in private law. When she changed careers a few years later, her fellow alumnae were a welcome presence, she said.

“It was nice to have a built-in community to turn to for advice and guidance in a very new role for me,” she said. “And Joanna and Mei Lin were just tremendous resources of advice and friendship and rapport in what was a very challenging position.”

Decades later, they are still trusted sounding boards for each other. James recently came across an unusual procedural matter in a case and asked Hendon for her thoughts.

“It’s very difficult to know at 25 or 26 what kind of lawyer you actually want to be over a career that, with luck, will span 30 or 40 years. But if you surround yourself with the highest quality supervisors or mentors to learn from, I don’t think you can go wrong.”

—Joanna C. Hendon ’91

“That I can and do still reach out to her in that regard is the outgrowth of a long relationship,” James said. “And I’ve had equally great professional experiences with Mei Lin.”

Over the years, the shared experiences mounted. Hendon and James have been guest lecturers together for a criminal defense class at the Law School. And they serve together on the board of the New York Council of Defense Lawyers.

“As women in the profession, we have an increasing number of common experiences and shared war stories — and Dani is someone I admire enormously,” Hendon said.

The three have continued to find ways to work together. Soon after both had left the prosecutor’s office in the early 2000s and were criminal defense lawyers at separate firms, Kwan-Gett alerted Hendon to two cases. Kwan-Gett would represent the corporation at the center of each matter, while Hendon represented witnesses or individuals being investigated. Hendon came away impressed by her friend’s defense work after seeing it up close and still appreciates that early opportunity.

“In that role, Mei Lin really supported my career, and I have looked for ways to support hers in return,” Hendon said.

Those two cases, one entailing allegations of public corruption and the other involving securities fraud allegations, were the first of several in which Hendon and Kwan-Gett have had clients who were subjects of the same investigation or litigation.

“In those circumstances, our shared experiences really help us to work easily together on arguments and strategies — ultimately helping us to be the most effective advocates for our clients,” Kwan-Gett said.

The three may never have worked together at all had their careers followed the trajectory they envisioned for themselves after law school.

Hendon at one point thought she wanted to be a law professor. But after a summer associateship, she came to love litigation, drawn to the challenge and drama of the courtroom and the intellectual problem-solving of piecing together the events of a case.

At her first firm after law school, James worked for a time on civil cases, which made her doubt she wanted to be a lawyer. “But that wasn’t true,” she said. “I was just doing the wrong kind of lawyering.”

James later found herself drawn to news stories about white collar crime and what she called “business scandal” books and realized she wanted to be prosecutor.

Kwan-Gett, on the other hand — like many of her classmates, she said — did not have a specific career path in mind while in law school. Instead, she took her career one step at a time. As a result, Kwan-Gett noted, she has been able to enjoy seven different jobs ranging from First Amendment fellow at the ACLU to Special Investigative Counsel at the Department of Justice.

“I think it’s important to be open to the wide variety of opportunities the legal profession offers, and to understand that different jobs will appeal to you as your skill set, experience, and worldview grow,” Kwan-Gett said. “It’s worth taking some risks now and then.”

“Even if we weren’t in the same field, their advice is something I’d value. But it’s amplified by our background as women in this field.” —Dani R. James ’95

Hendon and James said that planning one’s career can be helpful — to a point. Both have had to make sudden shifts over the course of their working lives. Hendon, for instance, found herself having to look for a job when the financial services firm where she was in-house counsel folded following the 2008 recession. James pivoted to teaching after taking time off from work after the birth of her first child, which coincided with being uprooted by a cross-country relocation. Instead of rigid plans, all three stressed flexibility and openness to new experiences, especially when starting out.

“What’s most important is to like, respect, and feel you are learning from those around you, now, in whatever role you currently have. It’s very difficult to know at 25 or 26 what kind of lawyer you actually want to be over a career that, with luck, will span 30 or 40 years,” Hendon said. “But if you surround yourself with the highest quality supervisors or mentors to learn from, I don’t think you can go wrong.”

The three lawyers said it also helps to have peers who can serve as examples.

“I find that every job change requires a leap of faith to some extent,” Kwan-Gett said. “It’s so much easier to take that leap when a friend has made a similar move — and you can see them thriving.”

Those shared experiences — as Yale Law School alumnae, prosecutors, white-collar defense lawyers, law firm partners — helped form their friendship, but they don’t fully explain why it has lasted through the highs and lows of work and life. It’s more than that, James said.

“It’s a reflection of who they are — their warmth, their kindness, their intellect, and judgment,” James said. “Even if we weren’t in the same field, their advice is something I’d value. But it’s amplified by our background as women in this field.”