Evan Wolfson Discusses Recent Trip to China with the Tsai Center

“Today, in the name of love, the Rainbow Law School invites you,” read the post blasted across Chinese social media. It was a strong opening for a novel idea: an intensive four-day seminar in Beijing In addition to inviting local lawyers and professors to join as speakers, Rainbow Law School’s organizers were eager for a particular special guest to engage with students about what makes a social change movement successful: Evan Wolfson.

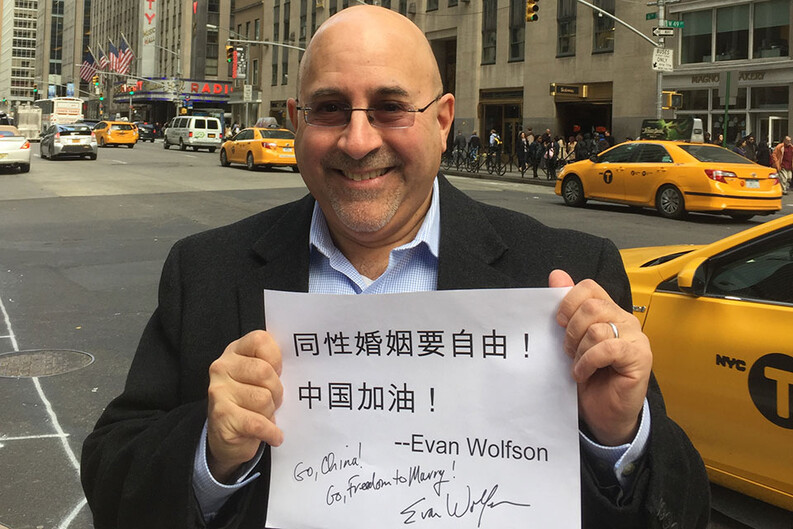

The founder and president of Freedom to Marry, Wolfson is widely considered to be the architect of the campaign to win gay marriage in the United States, a battle he fought for 32 years from his days at Harvard Law School through final victory at the Supreme Court in 2015. Since then, Wolfson has been teaching strategy and change at Yale and Georgetown Law, while spending the bulk of his time advising diverse causes in the United States, as well as LGBT rights advocates around the world, including in China. Under the auspices of the Paul Tsai China Center, Wolfson and Tsai Center Senior Fellow Darius Longarino joined Rainbow Law School in July 2018. And on October 1, 2018 they held a lunch talk at the Tsai Center to discuss their trip.

Wolfson was not surprised by the mobilizing power of marriage. Repeating a view he often shared at Rainbow Law School, Wolfson said to attendees at the Tsai Center, “Marriage is both a goal and a strategy. By fighting for the freedom to marry, we are laying claim to a vocabulary — of love, of family, of community — that transforms non-gay people’s understanding of who gay and transgender people are.”

“It creates more space for conversations about the reality and diversity of gay and transgender people’s lives, and about shared values,” he continued. “And conversation is the engine of change.”

While at Rainbow Law School, Wolfson suggested advocates find ways to talk more the freedom to marry in China as a way to grow wider public support for LGBT movement.

When asked at the lunch talk about China’s tightening political environment, Longarino and Wolfson expressed cautious optimism for China’s LGBT movement. Longarino noted that social attitudes are improving and that, although many obstacles remain, there are some positive signals from government entities — whether in the form of court decisions or public statements—that are encouraging.

Wolfson maintained hope in the ability of LGBT advocates in China to effectively engage communities and further transform public opinion. He also highlighted the vastly different global context of today than at the time of Stonewall: “Today, the world and China are integrated with each other, and there are over a billion people living in jurisdictions where gay people share in the freedom to marry.”

“Communist one-party states like Cuba and Vietnam are discussing the freedom to marry. Taiwan is about to have marriage for same-sex couples. It’s a discussion China cannot ignore. The what Chinese advocates have to do is the same — grow understanding and empathy, as we have had to do everywhere. The how will be different, as in every country, making use of what is available in the Chinese system. That is what they need to figure out and explore.”