Fellow Spotlight: Robina Postgraduate Fellow Mara Redlich Revkin ’16

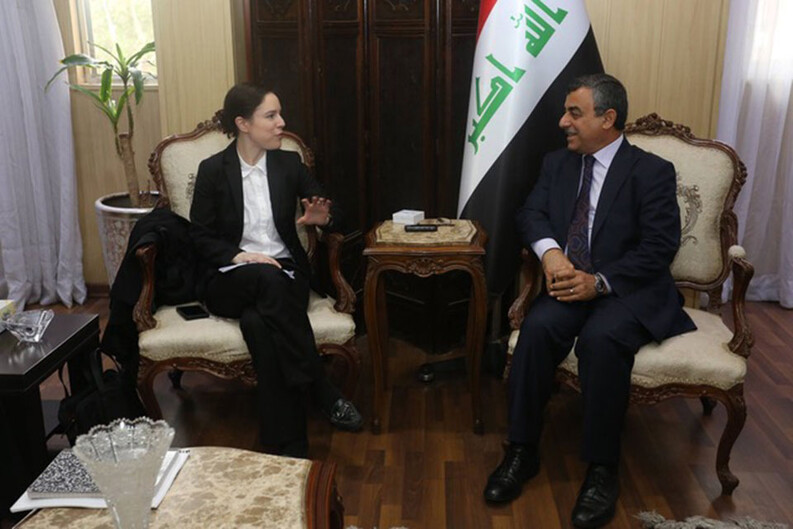

Mara Redlich Revkin ’16, a 2019 Robina Fellow, spent her fellowship working in Iraq with her partner organization, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), conducting research on the question of whether community policing methods can improve relations between civilians and police in the post-conflict setting of Iraq, therefore improving both security and the protection of human rights.

Through a research partnership she began with IOM’s Iraq mission and the Law School’s Center for Global Legal Challenges in the summer of 2018, Revkin led a multi-method study to assess the effects of a community policing program that IOM is implementing with the cooperation of Iraq’s Interior Ministry. The program aims to improve the relationship between Iraqi police and civilians by training police officers in principles of community-oriented policing including the importance of procedural justice, human rights, and gender sensitivity. For Revkin, the project was “an exciting opportunity to apply my training in political science research methods and data analysis to help a humanitarian organization develop evidence-based programs to address urgent human rights issues in Iraq.”

At Yale Law School, Revkin was a member of the Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic and spent a summer interning at the Cairo office of Human Rights Watch. She also led research on transitional justice and the recruitment of children by armed groups in Iraq and Syria for United Nations University, the research wing of the U.N.

Revkin also earned a Ph.D. in Political Science from Yale in 2019 with a dissertation on the Islamic State’s system of governance in Iraq and Syria. Her political science research focuses on the development of evidence-based policies and programs that can promote the protection of human rights and rule of law in war-torn societies. While finishing her Ph.D., Revkin moved to Iraq for a year in January 2019 to be able to work more closely with IOM on the implementation of the study of community policing

The objective of the community policing program was to try to improve relationships between police and people, Revkin said, following a “long history of human rights abuses” by police during and since Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship. While Iraq established a democratic government in 2003, Revkin said that reforming “a historically abusive security apparatus” has proved difficult and requires fundamental institutional changes. Iraq’s Interior Ministry has taken the positive step of establishing a community policing division dedicated to building trust between police and civilians, but more reforms are needed. According to Revkin, Iraqi security forces have used excessive force and violence against anti-government protesters as well as civilians who are suspected of supporting the Islamic State.

As a researcher, Revkin and her team at IOM wanted to collect data to evaluate whether or not this community policing program, once implemented, would in fact be effective in improving the relationship between civilians and police in several areas including mutual trust, cooperation, fairness, and gender sensitivity. The multi-method study included interviews, focus groups, and door-to-door household surveys in thirteen Iraqi communities where the community policing program was implemented. Data was collected at two different points in time, before and after the start of the six-month community policing program, to measure changes over time. The results, Revkin said, provide some evidence that community policing can improve civilian-police relations, “which is an important step toward improving the protection of human rights in Iraq.”

The survey questions asked community members questions about their individual perceptions of local authorities and police including, but not limited to, whether or not they felt safe, whether or not they viewed the community policing as legitimate, responsive, trustworthy, and fair, and whether or not they respect and cooperate with police voluntarily.

Because of limitations of the methodology and “confounding variables” that are inevitable in “the challenging real-world environment of Iraq as opposed to a laboratory,” Revkin said, definitively identifying the effects of the community policing program is not possible. Still, the data and observations provide suggestive evidence that the program is having a positive impact on civilian-police relations and is also “helping us understand the context in which IOM and other organizations are trying to work on security sector reform and post-conflict stabilization in Iraq.” The study also provides “insight into the needs and experiences” of Iraqis surveyed, which is essential for developing evidence-based programs and policies that respond to Iraqis’ concerns.

According to Revkin, the results of the study show that Iraqis are “very concerned about the protection of human rights,” especially in areas “where state security forces and other militias have used violence to repress peaceful anti-government demonstrations.” In areas where the community policing program was implemented, there were some significant improvements in perceptions of safety, willingness to report crimes, and trust in the police, suggesting that “training police officers in principles of community-oriented policing is a promising tool for security sector reform in Iraq.” Currently, this training is only being provided to a “select group” of police officers and this study will help support IOM’s efforts to provide this training to “all Iraqi police as part of a comprehensive strategy for security sector reform.”

The study also found that women are significantly more willing to report problems to female police officers than to their male counterparts. This finding, according to Revkin, is most likely a result of both “the stigmatization of gender-based violence” and “conservative social norms” that discourage interaction between women and men outside of their households. This finding is particularly important in light of reports of an increase in domestic violence in Iraq since the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus.

“Since only 2 percent of Iraqi police are women,” Revkin said, “training more female police officers and increasing the representation of women in traditionally male-dominated security institutions could significantly increase the likelihood that women who witness or experience crimes would report those crimes to police. In addition to making women safer, this would also improve security for everyone.”

Another important finding is that despite significant demographic differences between the communities included in the study—including urban and rural areas as well as Christian-majority, Sunni-majority, and Shia-majority areas—there were some common concerns and grievances: government corruption, unemployment, quality of basic services, and public health — the latter of which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Revkin had expected to see the most severe grievances in the Sunni-majority northern areas of Iraq that were captured and controlled by ISIS between 2014 and 2017, because these areas had experienced economic neglect and repression by the central government in the years leading up to 2014. She was thus surprised when the results of the baseline surveys conducted in July and August 2019 showed the “biggest grievances in terms of corruption, services, and the economy concentrated in Shia-majority southern communities.” These findings turned out to be prescient a few months later in October, when anti-government protests swept across central and southern Iraq motivated by the same grievances documented in the surveys.

After conducting research with IOM, Revkin has reflected on the importance of empirical research and data collection for humanitarian and human rights organizations. “Whether collecting evidence of human rights abuses to hold governments accountable or collecting data to measure the impact and effectiveness of humanitarian programs,” Revkin said, “organizations are increasingly interested in doing rigorous research to support evidence-based programming and advocacy.” She is grateful that, through IOM, she was able to “apply the research skills [she has] developed as a political scientist” to support an organization that is doing important work on the protection of human rights in Iraq. Revkin is now a National Security Law Fellow at the Georgetown University Law Center where she is continuing her research on police reform, rule of law, and human rights in Iraq.