Q&A: Bayla and Andis Arietta Raise Awareness of Bird Fatalities Through Art

Andis Arietta, PhD ’22, and Bayla Arietta are Law, Ethics & Animals Program4 (LEAP) student grant 5recipients. Andis studies evolutionary ecology at the Yale School of the Environment and Bayla is a curatorial assistant at the Yale Center for British Art as well as a scientific illustrator. Over the past year, they have ideated, planned, and commissioned pieces for Fractured Aviary6, a collaborative art show devoted to raising awareness about bird window strike fatalities. The show opens June 30. The seed of the project began while documenting window strikes on Yale’s campus, an effort that has recently expanded with the launch of the Yale Bird-Friendly Building Initiative7. LEAP Program Fellow Noah Macey spoke with the Ariettas about the gallery project. Their conversation has been edited for clarity.

Could you give a brief description of your project? What’s the status of the gallery and how has the commission process been going?

The preliminary spark for all of this is that we were working from home during the pandemic and wanted to get outside. So we started walking down to the Yale School of Management, and we found a dead bird — a black and white warbler — that we removed. Andis was doing graduate work at the Peabody Museum, so he took the warbler there. Through the Peabody we connected with Viveca Morris, who was also collecting birds killed by the School of Management for the Peabody. That kind of snowballed into a bigger project: we realized that if we did a more systematic recovery of the birds being dispatched by that building, we could actually get an estimate of the death toll — a lot of problems with this type of work is that unsystematic dead bird surveys can give poor estimates of how many birds actually die. You can miss a bunch — maybe there’s landscaping going on that removes them, or cats, birds of prey, or janitorial staff take them away. So Viveca and her partner would go out in the morning, then we would head out in the evening — we did surveys twice a day.

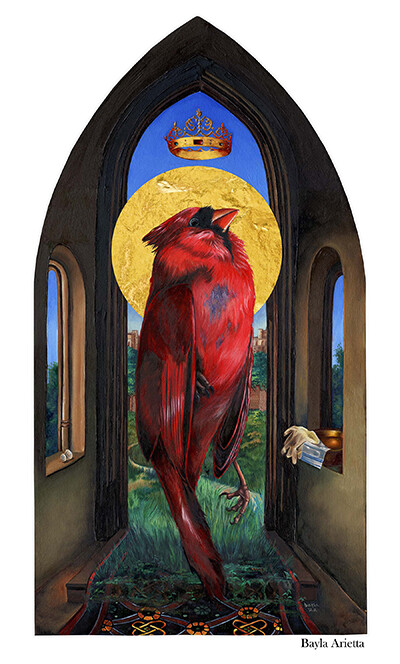

Bayla Arietta

Watercolor, oil, and 23k gold leaf on birch panel, 2022

Through all that, there was a day when we decided to start painting them. Bayla is an artist and became more interested in creating images of the bird crisis. We learned more and more about how many birds in the United States are dying from flying into windows, and that there are solutions that can fix the problem for most buildings — the School of Management has been asked to make those changes many times but isn’t doing any of them. Then we heard about the LEAP grant program8 and thought it might be interesting to take this idea and reach out to other artists and to a gallery. We wanted to build some awareness of the issue in the art world.

We reached out to Antler and Talon galleries6 in Oregon — they’re side by side and owned by the same people. We wound up having so many interested artists that they’re letting us use both spaces: it’s going to be a huge show. We have about sixty artists creating work right now. Many have already finished, and everything is being shipped to the galleries for the opening on June 30.

What kind of media are the artists working in? Were they mostly familiar with the window strike problem already?

We have a really wide range of work, which is exciting. There’s a lot of two-dimensional art: watercolor and oil paintings, but we also have some sculptural artists and a couple taxidermists. Bayla reached out to a few different people who are ethical taxidermists, so they work with birds that have died by window strikes or some other sort of natural death. Those artists were well aware of these issues already because it’s how they find lots of the birds they work with.

A lot of the artists that we picked were focused on environmental work, so many of them were aware of the window strike problem. Others maybe didn’t know about it ahead of time, but became passionate about the idea upon learning more, and that’s the whole point of the LEAP grant and this project: to make sure people become more aware of the issue. It’s the buildings they live and work in that cause this problem; it’s happening all around us. We’ve given artists the freedom to look at what’s going on in their home countries as well–the show isn’t about birds in the Connecticut region, or even in the United States.

We picked the gallery that we did because they highlight environmental issues, though they’d never done anything exactly like this. They had worked with the Audubon Society in the past for a bird-related show, but it wasn’t about bird mortality.

Could you sketch the outlines of the scale of the window strike issue, for people who aren’t familiar with it already? What are the possible fixes for the problem?

It’s estimated that one billion birds a year in the United States alone are killed by window collisions. Other than domestic cats (which is about an order of magnitude higher), it’s the leading cause of wild bird mortality.

As far as solutions: there’s window decals, netting, films you can put over windows. Ultimately, the easiest thing to do is just to design the building well. Yale is an interesting example because we have many different types of buildings. The buildings that are really gothic, that borrow from old-school architecture, have no bird problems because they have small windows with lots of pane outlines, so birds see them. It’s the more modern style with glass facades everywhere that creates huge issues. The Yale School of Management is not only an all-glass facade, but it has an interior courtyard too — I wouldn’t be surprised if a few people walk into those windows every year; it’s so easy to imagine a bird on the wing smashing into one of them at many miles an hour.

What are some ways people can get involved with this issue?

Well, entry to the gallery is free. And if readers have interest in this but aren’t in Oregon, they can reserve just a modicum of the time that they’d spend looking at the art to send a quick email to either the City of New Haven9 in particular or even one of the state representatives10 to say, “Hey, I heard that birds striking buildings is a huge issue in the state, and I would love to see policies enacted to help address this problem.” It can be as short as that — a lot of people just don’t know it’s an issue. So as far as involving policymakers and people who are designing buildings, just having enough people interested will do quite a bit: they’ll learn that people care, and it could do a lot to change the problem.

If people want to register bird strikes, iNaturalist11 has a phone app that you can use to take photos of birds and upload them to the database. You can get it on any mobile device, and the AI will help you figure out what the species is, then experts on the site will verify it. The upload has geolocation, so you can mark where the bird’s body was found. Then, there are people who will collate the observations in a given city into localized projects — either a window-strike project or a mortality project. This winds up being a good way to accumulate some citizen science on the topic and to make sure that your observations are being stored. In New Haven, specifically, there is a bird window-strike group, so if you log an observation in New Haven, one of the folks there will find it and curate the data point for the project.

If folks are really energized and want to do more, they can find a natural history museum and ask if they’d like to collect the specimens12. One of the problems is that a lot of these birds are endangered or migratory, so they’re protected, and you can’t just go around and pick them up on your own. You can take photos, which is why iNaturalist is great, but if you’re going to be collecting you really want to be working with a natural history museum, researchers, university, or even a state agency. It’s illegal to have bird parts from these species—the idea to keep people from going out and collecting birds. So you don’t want to be walking around with a specimen, even if you’re not doing anything nefarious… Enforcement officers won’t know that. You want to work with people who already have collecting permits, like museums.

Now, if you find a stunned bird, the thing you should probably do is just leave it be. If it’s baking in the hot sun on concrete, or in a high traffic area, then you can move it someplace close by in shade or out of the way. Then just wait an hour, because a lot of birds will be fine. They’ve just had the wind knocked out of them, and then they’ll go on their way. If they’re still there after an hour, you can contact local exotic vets or a local vet, or the local Audubon Society, who might be able to find a rehabilitator. Unfortunately, sometimes you just have to leave them and let nature take its course, which is a real bummer, but that’s why we need to fix the problem in the first place.

Also, if you’re concerned about the issue, and you have cats who you let outside—maybe bring them inside. The scale of that problem is even larger than window strikes.

Has working on this changed the way you see the interaction between animals and urban space?

Yes, it literally changes how you walk around — we’re always looking to the margins of buildings. More than anything, talking about this led us to think differently about the problem and about the solutions. It’s odd how recalcitrant a lot of architects and building managers are to even realizing they have a problem. That’s the biggest hurdle — a lot of folks think it’s easier to skate around the problem than to address it, which is really unfortunate. And because there haven’t been a lot of big-scale experiments, it’s really easy to put off a solution under the guise that we don’t know enough about what would work.

For this project in particular, it’s less about discussing the sheer number of birds and more about the individual birds. One time, by SOM, we found this female ruby-throated hummingbird that had obviously hit the building, and her beak was broken down, and it was just the most tragic thing. She could just fit in the palm of your hand. And this bird — you can imagine her last moments. She’s at the start of spring, getting ready to breed, and then this happens. It’s tragic. And you often see stunned birds that probably won’t survive, and that’s even more heartbreaking. You pick up these birds and try to figure out whether they’re going to die, whether you should try to find a rehabilitator…It’s so stressful we prefer going to look for birds in the afternoon because at that point they’ve already died and you’re just counting them. In the morning, you have a much higher chance of running into injured birds that are still alive.

It’s easy to show people numbers about bird strikes, but when you actually see some of the birds and piece together their individual history with what’s going on, it can be really heartbreaking. Hopefully that will move more people to care about the issue.