Q&A: LEAP Student Grant Winner Kevin Yang on Designing for Nonhuman Animals

Kevin Yang (M.Arch. ’24) is a Master of Architecture candidate at the Yale School of Architecture and a Law, Ethics, & Animals Program (LEAP) 2022 Student Grant recipient. In collaboration with the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History4 and the Yale Center for Engineering Innovation & Design (CEID)5, Yang initially sought to design and deploy model structures to encourage human-animal cohabitation in urban environments and provide shelter for nonhuman animals. His project has evolved to create and deploy structures that reclaim human-dominated spaces for nonhuman animals.

LEAP Postgraduate Fellow Laurie Sellars spoke with Yang about his LEAP student grant research. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

Could you give a description of your project? How has your vision developed over time?

At the core of this project is the question of what it means to design for animals. While in the past we designed dovecotes and housebarns for animals to inhabit, architecture as we know and practice today is incredibly human-centric. With the influences of modernism and its embodiment of rationality, sterility, and progress, eaves and ornamentation have turned to smooth facades of concrete and glass. Our built environments block migration pathways, fragment habitats through sprawl and development, and are responsible for the death of billions of birds each year from window-strikes. Continuing to build in this manner — with the assumption that human spaces are disconnected from that of the natural world — is incredibly short-sighted. And with climate change further destroying habitats and displacing animals, human and non-human species will only be forced into greater confrontation.

This project initially began as an exploration of building “architecture” for animals, drawing upon the structure, material, and methods of animals to construct dwellings for non-human species that integrate into the built environment as a sort of cohabitation. However, as I spent more and more time at the Peabody learning about the complexity and genius of birds and insects, this project became less about designing replacement structures for animals and more about reclaiming space from the built environment for non-human species.

“With climate change further destroying habitats and displacing animals, human and non-human species will only be forced into greater confrontation.”

— LEAP Student Grant Recipient Kevin Yang

One of the guiding questions was what role human attention and perception play in the project: would this be something eye-catching that raises awareness for themes of animal-human cohabitation, or would it be solely dedicated to animals, out of sight and mind for people? I ended up approaching this from a framework of climate literacy and human interaction with nature, aiming not only to share insights into the non-human world, but also critique cultural behaviors in present society. Why is there this obsession over lawns, which are vestiges of 18th century status-signaling by the aristocracy? And why is there such obsession by architects over the usage and aesthetic of glass? I hoped this human-centric approach could engage with more people who might then push these ideas further, rather than limiting the scope of impact to a single person.

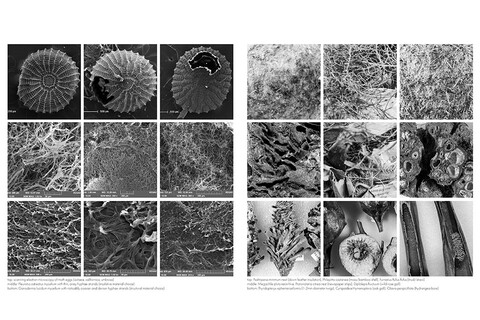

For a time, I also wanted to explore the perceptions that people have of certain species, such as the fear and inherent repulsion that people have for house spiders. I wanted to do something provocative that demonstrates the benefit that spiders and other insects have for not only us, but also ecosystems at large. So I considered making a spider hotel that fits into the corners of a room, thinking that the emphasis on presence and this “signaling” or “announcing” of the spider might make people feel like it is less of an uninvited guest. That is still developing, as I think it would be a fun project. But currently my focus is on a more integrated approach to nature and ecosystems. Some of the most beautiful specimens at the Peabody Museum are the moth eggs, and scanning electron microscope (SEM) images reveal these incredibly intricate details that help prevent the formation of frost when overwintering. I wanted to try to make visible the seemingly invisible and share the beauty of these structures. Currently, this project has taken the moth egg and enlarged it into a sculptural form that can be placed in spaces of the built environment such that the interstitial spaces between the structures reclaim territory from human spaces (e.g., lawns) and return them to non-human use.

What factors did you have to consider in imagining structures that would benefit nonhuman animals?

With the initial project idea being to develop a structure for animals, I spent my summer months at the Yale Peabody Museum collections studying the ornithology and entomology collections. The Peabody has these cabinets of specimens that you can lose yourself in, with drawers of hundred-year-old specimens, their nests, of birds, eggs, insects, and so much more. It would take a literal lifetime to work through everything, and I was lucky enough to have Kristof Zyskowski and Larry Gall, incredibly knowledgeable collection managers at the Peabody Museum, guide me through the specimens that were most relevant.

I learned about species such as the velvet asity bird (Philepitta castanea) from Uruguay that builds nests that hang from a single leaf, using various grasses and bamboo leaves to make the inner cavity waterproof and constructing an awning with decorative grasses perhaps to camouflage from predators while also attracting mates. The ovenbird (Funarius rufus rufus), as another example, uses thousands of beakfulls of clay to build clay nests, complete with false entrances and fully stackable into little “hotels.” I learned about the shaping of bird eggs such that they roll in circles (instead of off a cliff), how some birds use their down feathers to insulate their nests, how some bird nests are used by other species such as frogs and mice after the nests are abandoned. Larry also showed me how insects such as butterflies and beetles have structures that produce patterns in the UV-wavelength that are invisible to the naked eye, which prompted the interest in making the invisible, visible.

Additionally, I learned that one of the limiting factors for animals is the suitability of spaces to construct their dwellings. For example, some cavity-dwelling birds require snags (downed trees) of a certain diameter as a host for their cavities. The number of these large trees is actually a limiting factor, and one potential project direction was to make structures in the Yale-Meyers Forest that provided these larger diameter tree sections. However, I felt that this approach would be more isolated and limited in its engagement with people, and with the project’s focus on climate communication I ultimately chose to pivot to a new direction.

At the core of this incredibly diverse range of inventions are key principles that shape the structures: environment (weather, temperature, climate), predation (camouflage, material selection, placement of structure), and mating (decoration/ornamentation). There was so much to work with and consider that it became difficult to make a decision. And ultimately, in realizing the diversity, intricacy, and genius that came with these incredible structures, what seemed to be important began to be less and less about designing a space, when our techniques could never come close to what eons of evolution has honed. Additionally, the needs of animals extend beyond just shelter, to mating and feeding grounds. After speaking with some professors, I shifted the project away from designing a structure that housed select species to one that captured urban space to foster habitats and ecosystems.

You considered a variety of materials for building these structures. What kinds of materials have you looked into and why? How do you turn these materials into useable structures?

Because of the complexity of these structures, I turned to clay 3D printing to produce more intricate structures than ones made by hand. The clay is left unfired to reduce the embodied energy of the structures and seeded with mycelium in a growth chamber to develop a thin, protective coating for nature to gain foothold for growth. Thanks to CEID and Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science, I was able to spend time over the summer testing whether mycelium would be able to grow on various 3-D printed substrates. I had initially partnered with a Ph.D. student in the chemistry department to explore biopolymers as a building material, but unfortunately the proof-of-concepts didn't pan out and I had to turn to clay and mycelium. Because the clay is an inorganic material, the mycelium does not consume the clay but rather draws on nutrients from its grain spawn substrate to cover the clay in a mycelia sheath.

What was the inspiration for this project? Did any particular event, place, or animal spark your thinking about shelters for nonhuman animals?

“I grew up in California, and in recent years the wildfire seasons have been incredibly severe. Recently one of the parks I'd spent time in as a child was devastated by a wildfire, and this event made me want to do something to provide shelter and space for animals.”

—LEAP Student Grant Recipient Kevin Yang

The inspiration for this project really began with my studio project during my first year of architecture school. The prompt was to design a research space to host a human researcher, birds, and John Jay Audubon’s book Birds of America. My site was located at the English Station on Ball Island in New Haven, and I designed this contraption to slowly make its way around the perimeter of the site, remediating the contaminated land through a system of phytoremediation that also incorporated the interactions of species such as mealworms, bobolinks, and peregrine falcons. Through this studio, I was introduced to the Peabody Museum and the Yale-Myers Forest6, both of which are incredible spaces and laboratories of learning. Beyond the academics, I had a personal interest in this project stemming from an environmental preservationist lens. I grew up in California, and in recent years the wildfire seasons have been incredibly severe. Recently one of the parks I'd spent time in as a child was devastated by a wildfire, and this event and the imagery of animals escaping the bushfires in Australia made me want to do something to provide shelter and space for animals. Architecture as it currently stands is not in alignment with the flows and processes of nature, and my hope is to incorporate this sensitivity toward nature into future practice.

What are the future plans for this project? Will the Yale community/public be able to come and see your designs in person?

Currently this is the first iteration of what I hope to be a lifelong engagement. I’m printing a series of enlarged moth eggs and scattering them around lawns and pathways in Yale and New Haven so they will be out and about, attempting to carve out spaces for native species. Some key places are along the Farmington Canal Trail, the Shelton Learning Corridor, and some courtyards of Yale. I'm curious to see whether they will function as intended: Will they be durable enough to endure the seasons, or will they wash away at the first summer storm? If these work as intended and I can build up documentation of their use by plants, insects, and animals, I'd love for them to be exhibited to the public at the opening of the Peabody Museum.

What, if anything, has your work on this project taught you about the nonhuman world? Was there anything that surprised you?

It's a little tricky to say, since everything about the non-human world was so fascinating. Every time I went to the Peabody I was learning something new, and it affirmed the complexity of the natural world and its relationships. We see the importance and interconnectedness of nature through the impacts of removing capstone species, such as wolves in Yellowstone, or the extinction of the passenger pigeon. And at the end of the day, it is this wealth of networks and relationships in nature that stabilize and ensure the functioning of the world. I think that architecture and modern life have put us in a state of isolation from nature, weakening and really severing our relationship with the world (both socially and environmentally), and we insulate ourselves from the loss of biodiversity in the world. We only do ourselves a disservice by not realizing the importance of nature, as it is this biodiversity and its networks that also sustains our lives.