View major milestones in the history of Yale Law School over the past 200 years through archival research conducted by the Lillian Goldman Law Library.

Guido Calabresi ’58 often quotes Grant Gilmore ’43, a renowned faculty member and graduate of Yale Law School, known for saying, “The golden age of Yale Law School is never now. It was always in the past and can be again in the future if we only do a few things right. Always trying, always striving, never quite there except in memory and hope.”

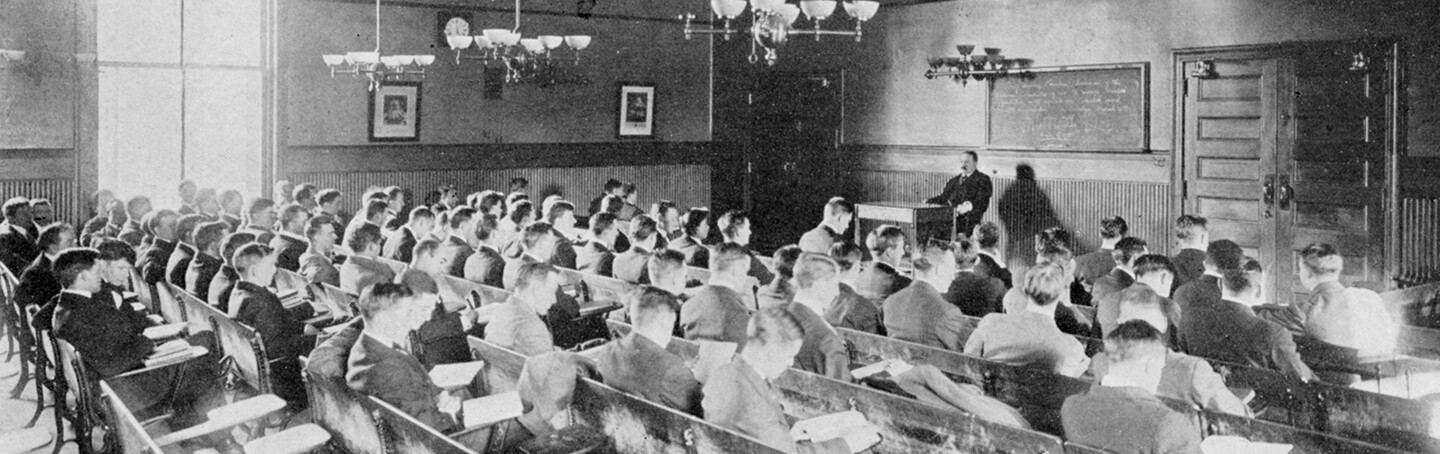

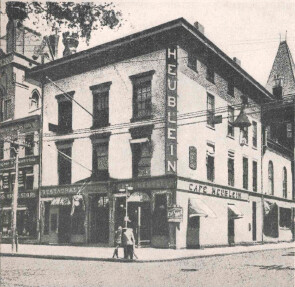

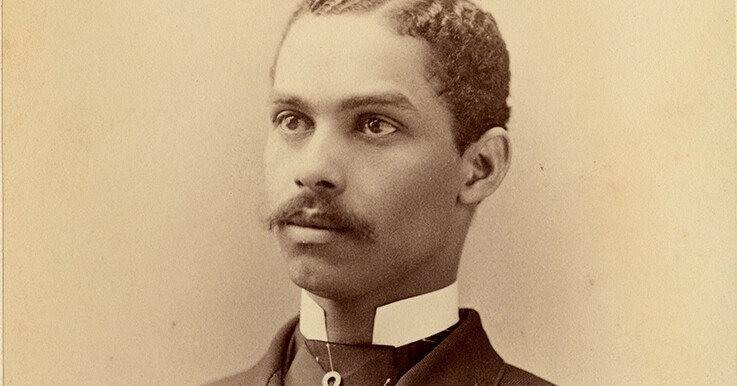

This “restless spirit,” as Dean Heather K. Gerken calls it, has been the driving force for the Law School since its early beginnings. What started out as a tiny school that nearly didn’t survive, operating out of a rented room over a downtown saloon, transformed over time into a premier law school that has shaped the minds of leaders and changemakers across every sector of society.

“The Law School has shown a remarkable power to rejuvenate, even to reinvent itself,” said Anthony T. Kronman ’75, who served as Dean from 1994–2004. “This always comes with challenges and risks. The older faculty want the traditions of the School to be maintained, but the most important of our traditions is the willingness to take risks and go out on a limb, and do the wild and crazy thing.”

Former Dean Harold Hongju Koh agrees that the Law School is never content to rest on its laurels: “If we didn't globalize, we'd become provincial. If we didn't get close to the profession, we'd be too ivory tower. If we didn't focus on public service, we would start to feel too mercenary. And if we didn't renew, we would become stale, by definition, less inclusive than the times would demand.”