Supermax Prison Closure Marks Success for Lowenstein Clinic Partners

In February, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont announced the closure of the state’s only supermax prison, Northern Correctional Institution. The decision represents a hard-fought success for local activists, who have spent years organizing against the highly restrictive prison and against the state’s use of solitary confinement more broadly. For the past decade, the Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic has supported these efforts. Since the Lowenstein Clinic began investigating Northern, more than 50 students have worked in partnership with the local movement that is now celebrating the closure of Connecticut’s only supermax facility.

“I am profoundly grateful for all those who helped secure my dream to shut down Northern, the supermax that robbed my 17-year-old son of his livelihood, humanity, and sound mind,” said Barbara Fair, an activist and member of Stop Solitary CT, who has been organizing against solitary confinement for more than two decades. “Northern is a place where state-sanctioned, sadistic practices leave young men with broken spirits and shattered minds.” Fair started working closely with the Lowenstein Clinic in 2016, when they collaborated on a campaign to pass anti-solitary legislation that resulted in a modest victory: a 2017 law improving transparency around restrictive housing and keeping minors out of administrative segregation, one of the Connecticut Department of Corrections’ (DOC) primary forms of long-term isolation.

“So many people have been integral to ensuring Northern’s closure...A decade’s worth of clinic student teams; tireless and awe-inspiring activists ... and above all, the courageous individuals we have met inside prison who fight to make their stories heard.”

—Hope Metcalf, Executive Director of the Schell Center

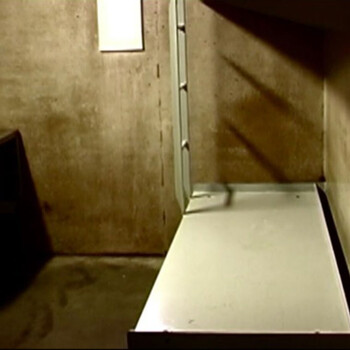

Northern was opened in 1995 to house the DOC’s highest-security prisoners, whom the DOC argued could not be managed elsewhere in the system. “From the beginning, the practices of prolonged isolation and in-cell shackling — where people are restrained in full-body chains inside a cell — were defining characteristics of Northern’s environment,” said Ify Chikezie ’22, a member of the Lowenstein Clinic. Fair explained, “The sole intent of [sending people to Northern] was to render them broken men.”

Beginning in 2010, Lowenstein Clinic students collaborated closely with the American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut to investigate conditions at Northern. “With a team of eight students, we spoke with dozens of men at Northern and gathered documents via public records requests,” said Hope Metcalf, Executive Director of the Schell Center for International Human Rights at Yale Law School. Metcalf co-teaches the Lowenstein Clinic and has supervised all of the student teams working on Northern. “Our findings were extremely disturbing,” Metcalf stated.

The Lowenstein Clinic found that DOC policies expressly permitted indefinite isolation and in-cell shackling. Lowenstein Clinic members learned that some individuals had entered Northern at ages as young as 17 and many stayed for years, often for minor offenses. “Northern warehoused many people with mental illness, whose mental health deteriorated due to the lack of care and the harsh conditions,” said Lowenstein Clinic member Luke Connell ’22. “In response to mental health crises, DOC staff — often with the blessing of medical staff — would use in-cell shackling, keeping people chained inside a cell with little range of movement for up to 72 hours. In recent years, those abusive practices have continued to be used routinely at Northern.”

Leighton Johnson, an organizer with Stop Solitary CT, was incarcerated at Northern at that time; he first got into contact with the Lowenstein Clinic when he wrote a letter to Metcalf in 2010. Since then, Johnson has left prison and dedicated himself to ending solitary confinement in Connecticut, continuing to partner with the Lowenstein Clinic through his activism with Stop Solitary CT. “I give a salute to every law student who worked on this since 2010 for not letting up on the system and for recognizing this as a human rights issue,” Johnson said.

The Lowenstein Clinic’s findings in this first investigation were the focus of a documentary by the Yale Visual Law Project, The Worst of the Worst. The investigation also supported the Lowenstein Clinic’s work advocating for the transfer of more than 20 individual clients out of Northern and negotiating with the DOC about reforms. But the team ultimately resigned from a reform-focused task force after the DOC was unwilling to implement sufficient policy changes.

Since 2017, the Lowenstein Clinic has sought other avenues to challenge human rights violations in Connecticut prisons and especially at Northern, including litigation and advocacy at the state and international levels. The Lowenstein Clinic submitted an allegation letter to the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture in 2019, arguing that conditions at the prison amounted to torture. The letter included direct testimony from 15 individuals who had been subjected to prolonged isolation in the Connecticut DOC. In early 2020, the Special Rapporteur released a statement condemning the DOC for “purposefully inflicting severe pain or suffering, physical or mental, which may well amount to torture."

“Everything that’s been happening to us has been forcibly silenced,” said Kezlyn Méndez, an incarcerated man who contributed testimony for the letter. “It’s important to me to expose how I’ve been mentally and physically victimized, a subject of Northern’s torture, so no one else becomes a subject of that torture and abuse.”

Kyle Lamar Paschal-Barros, who is still incarcerated at Northern while awaiting the facility’s closure, also submitted testimony for the letter. He emphasized the importance of making sure the public knows what’s happening to incarcerated people in real time: “We need to start asking what’s going wrong now. Often, we wait until it’s too late and ask what went wrong in the past. That’s how tragedy happens. When we know what’s going wrong right now, we can start to fix it.”

The Lowenstein Clinic has also supported efforts by Stop Solitary CT to pass anti-solitary legislation titled the PROTECT Act and the Lowenstein Clinic joined Disability Rights Connecticut and others in filing a recent lawsuit against the DOC. Northern’s closure was announced less than a week after the filing of the lawsuit, which challenges the prolonged isolation and in-cell shackling of prisoners with mental illness on isolative statuses.

“The successes of the past month — the filing of the lawsuit against the DOC and the announcement of Northern’s closure — are a powerful reminder that the years of work that have gone into Connecticut’s anti-solitary movement are bringing important and meaningful change,” said Zoe Rubin ’22, a member of the Lowenstein Clinic.

“So many people have been integral to ensuring Northern’s closure,” added Metcalf. “A decade’s worth of clinic student teams; tireless and awe-inspiring activists like Barbara Fair and Stop Solitary CT; and above all, the courageous individuals we have met inside prison who fight to make their stories heard.”

Now, the work continues, both for the Lowenstein Clinic and for its partners. “The main focus now is to make sure that the practice of in-celling and isolation don’t continue throughout the system,” said Johnson. “Northern was like the bogeyman. We killed that bogeyman, but there are other bogeymen, other monstrous practices, throughout the system that we need to get rid of.”

“The closing of Northern is a step forward in our quest for transformative change in how Connecticut treats incarcerated people,” expressed Barbara Fair. “For as long as prisons are the response to societal issues, our demands are that they operate by recognizing and uplifting the human dignity of all they hold in custody.”