Through Justice’s Papers, Students See Supreme Court Behind the Scenes

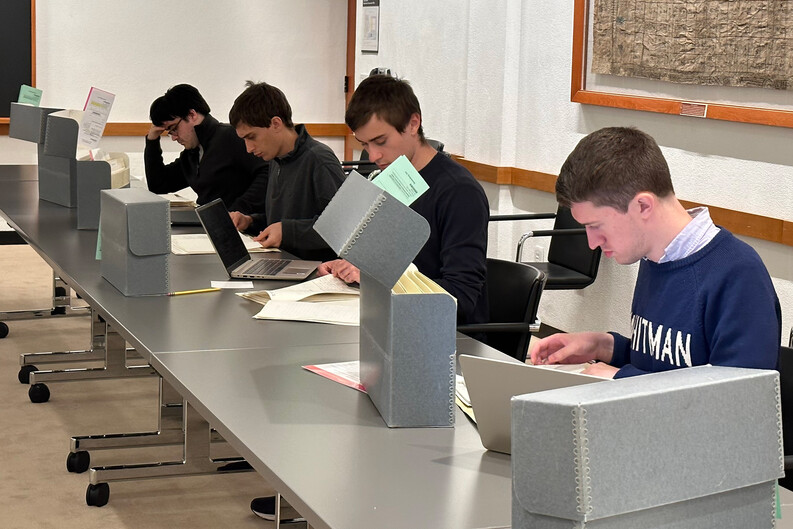

In a first-of-its-kind course this fall, Yale Law School students delved into the working papers of a former Supreme Court justice for an intimate view of the making of landmark decisions. Through hands-on use of these archival materials, students gained research skills once used mainly by scholars but now increasingly valuable for legal practitioners.

Taught by lecturers in legal research Nicholas Mignanelli and Michael VanderHeijden, Research Methods in Judicial History centered around the papers of Associate Justice Potter Stewart ’414, which are held at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Through Stewart’s papers, the course explored how judges and legal scholars use historical court materials to make sense of judicial decisions.

The 679 boxes of materials that comprise Stewart’s papers — Yale’s most extensive collection from a Supreme Court justice — span Stewart’s early life and time as an undergraduate at Yale through his retirement years. The bulk of the papers covers Stewart’s time on the 6th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals and on the Supreme Court, where he served from 1958 to 1981.

An “unfortunate source” increasingly used in court

Mignanelli and VanderHeijden were inspired to create the course when Chief Justice John Roberts cited correspondence5 in the private papers of former Associate Justice Harry A. Blackmun during oral arguments for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health last year. Roberts called papers “an unfortunate source,” in keeping with his previously stated dislike of courtroom references to materials outside of the published record. Even so, Roberts wanted to support his position6 that a key piece of Roe v. Wade could be discarded without undoing the 1973 landmark decision that legalized abortion nationwide.

The citation is a high-profile example of judicial history materials — documents generated by a court in the process of hearing and deciding a case, including personal papers — being used in court as a form of persuasion. These materials have long been key to the work of legal scholars and biographers, but judges and litigators are also starting to cite them more frequently, according to Mignanelli, Head of Reference at the Lillian Goldman Law Library.

“There’s this real interest in historical documents in appellate litigation right now and I think it does have something to do with the rise of originalism and textualism and not only bolstering that approach to law but also challenging that approach,” Mignanelli said.

Mignanelli knew of no other course in U.S. law schools that focuses on researching court documents and judicial papers and gives students the opportunity to do archival research in the papers of a Supreme Court justice.

The course frames judicial history as a counterpart to legislative history, the documents created by a legislature in the course of enacting a statute. That concept was first defined in a 1999 Yale Law Journal article7, which students read for the first class.

Everyday papers from a transformative period

Stewart’s papers and the transformative period they span lend themselves to exploration. During his years as a justice, the court handed down well-known decisions on issues including privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut), criminal trials (Gideon v. Wainwright), and the rights of people being arrested (Miranda v. Arizona).

“There’s a lot happening when he was on the courts — landmark decisions that have totally reshaped American life,” Mignanelli said. “He’s participating in all of them, he’s writing some of those decisions, and I think that’s what made it a really interesting collection for students to explore for themselves.”

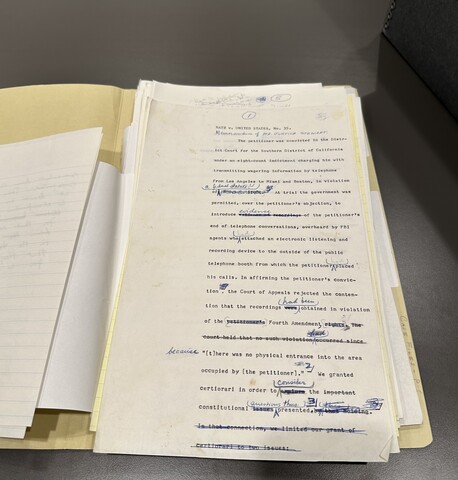

Among these is Katz v. United States, for which Stewart wrote the majority opinion. In this landmark case for privacy law, the court found that a wiretap on a public phone booth was unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures. Stewart also wrote the concurring opinion in Jacobellis v. Ohio. The line that summarizes Stewart’s test for obscenity is his most quoted in popular culture: “I know it when I see it.”

Mignanelli said that the original documents students were able to examine are the everyday output of a workplace, not so different than the those they might have worked with during their internships or summer jobs.

“I think it can be disarming how normal, how office-like these papers really are,” he said. “That kind of humanizes the courts. The Supreme Court is really just another working legal institution like any small law office in this country or any county trial court.”

Personal materials like letters from spouses and birthday cards also helped to show the human side of Supreme Court justices. Other biographical items included newspaper clippings, telegrams, photographs, and recordings of radio interviews.

Sonya Schoenberger ’24 looked through a folder containing correspondence between Stewart and Justice Hugo Black. She found the letters between Stewart and Black's widow, Elizabeth, particularly moving. Their words helped to shed light on the difficult personal choices that older justices face when to choosing when to retire, Schoenberger said.

From microfiche to information literacy

The course offered students the chance to hone practical skills like doing electronic docket searches and finding material across several jurisdictions. They also got practice in searching older forms of media like microfiche — which researchers regularly encounter in the many cases for which files will never be digitized.

The course’s instructors also hoped to give students an understanding of what information is available and how information is and is not preserved, VanderHeijden said.

“I think some basic education about the availability and maintenance of records is important whether you’re training to be an attorney or you’re a future researcher,” said VanderHeijden, Associate Director for Scholarly and Research Services at the Library.

Mignanelli added that it’s critical for students to have what he called “legal information literacy.”

“One thing we’re really focused on is teaching law students — teaching our future lawyers, litigators, judges, law professors, scholars — is to be critical consumers of information and to evaluate sources and resource tools so that they be more informed and they can make more informed and ethical decisions in their careers,” he said.

Going beyond the published opinion

Issac May ’24 came to the course well-versed in research, having written two academic books of history. May took the course to learn how to how to access judges’ papers and other legal primary source material for his research in American religious and legal history.

May said he learned that scholars and students often work with a more limited set of sources than most people realize. When someone talks about “reading a case,” they’re usually referring to reading a judge's published opinion. But the case’s related papers provide the complete picture of what happened, he said.

“Studying legal history, or even just understanding a legal case fully, requires working through a vast amount of material, much of which is not easy to access,” May said. “This course trained me to find the rest of the case and go beyond just the published opinion.”

May was interested in the 1963 case Abington School District v. Schempp, which ended teacher-led school prayer in public schools. From Stewart’s papers, he learned that Justice Arthur Goldberg sent all the justices a series of lectures on religious liberty by legal scholar Wilbur G. Katz. Some of Katz’s ideas from these lectures appear to have made it into the final decision, May noticed. By preserving Katz’s lectures, Stewart’s papers helped explain what ideas influenced the Supreme Court in deciding to end school prayer, May said.

Students who plan to be practitioners also found cases in line with their interests. Eamon Coburn ’25, who aims to become a labor lawyer, looked into the files for Fibreboard Paper Products Corporation v. National Labor Relations Board. In this landmark case for labor law, the court ruled that, under the National Labor Relations Act, companies must bargain with a union when hiring contractors to do the usual work of union employees.

To round out the course, guest speakers discussed the practice of research, the politics and policies of Supreme Court papers, and the technical details of archiving materials.

Students heard real-life tales of research by Clinical Lecturer in Law Linda Greenhouse ’78 MSL, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who has written about the Supreme Court for more than 50 years. Greenhouse talked about the excitement and the slog of researching her 2005 biography of Justice Harry A. Blackmun. She described hours, days, and years spent going to the Library of Congress, digging through papers, and making copies. Other than scanners and phones having replaced photocopiers, the process for researchers today is pretty much the same.

Students also heard from Eric Sonnenberg, a Yale archivist who has worked with law-related papers, about what it means to process, catalog, and preserve records.

“Students became fairly passionate about the process of archiving,” Mignanelli noted.

Another guest speaker was Susan deMaine, Director of the law library and Senior Lecturer in Law at Indiana University Maurer School of Law. DeMaine, who has written several articles on Supreme Court papers, explored questions including who owns the papers of justices and when should they be released. Unlike the papers of U.S. presidents, there are no rules for preserving papers of Supreme Court justices.

Schoenberger said the course made her think about how individual Supreme Court justices can shape the historical record with decisions about how, if, and on what timeline, their papers are made public.

“We had some interesting conversations about the larger implications of these individual choices for the historical record and for democracy,” Schoenberger said.