Weaponizing Information Conference: Watch Panel Videos and Read Summaries

On January 24, 2017, the Center for Global Legal Challenges, and the Information Society Project, co-hosted the “Weaponizing Information” conference. The conference examined how online propaganda, fake news, and disinformation campaigns are reshaping the legal and political calculus, as well as the relationship between international law, military strategy, and cyber conflict. The first panel examined different types of propaganda—from fake election stories to ISIS recruitment messages—and grappled with the difficulty of defining and responding to the problem. The second panel discussed propaganda in modern warfare and international law.

Watch the videos and read summaries for the panels below.

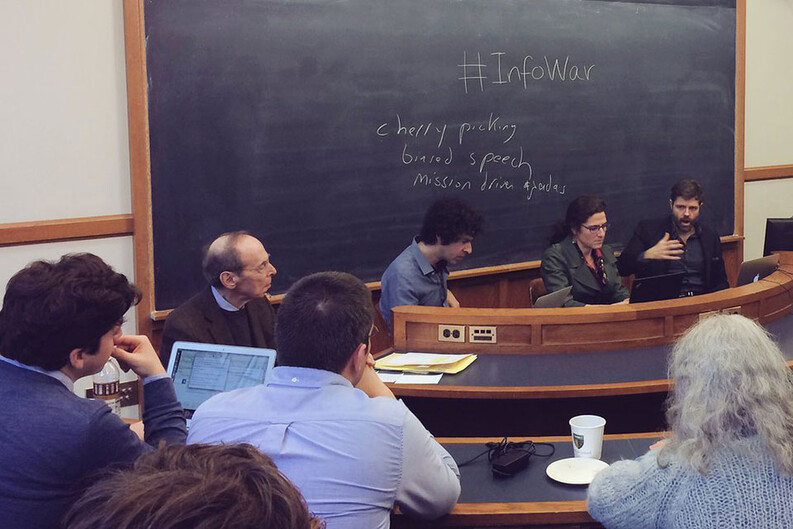

Panel 1: Manipulation and Misinformation: Propaganda and False News

Moderated by Professor Michael Reisman

Speakers: Professor Ellen Goodman, Rutgers Law; Professor Jason Stanley, Yale Department of Philosophy; Patrick Tucker, Defense One

The panelists discussed the difficulty of defining propaganda, how propaganda threatens democracy, and ways to combat it. Professor Stanley began by noting that people cannot avoid manipulating information as they speak; we emphasize certain facts and ideas over others, use labels to elicit different responses, and communicate specific messages. Thus, in the abstract it is difficult to distinguish between propaganda and normal speech, though implicitly the panelists agreed that the former involves deliberately distorting or disregarding the truth. Stanley argued that America is particularly vulnerable to propaganda because, unlike the laws of most other democracies, the First Amendment shields offensive and inflammatory speech. He noted that the Nazis took advantage of similarly muscular free speech protections to dismantle the Weimar Republic, leading Josef Goebbels to remark that democracies give their enemies the means of their own destruction.

Turning to propaganda in the 2016 election and its aftermath, Professor Goodman defined “fake news” as false statements borrowing from the authority of traditional media, authority that is itself under attack. Fake news thrives because it proliferates over the internet quickly and at no cost, and tools such as Photoshop make it easy to disguise a false story as a mainstream article. Goodman argued that this phenomenon circumvents the traditional, self-imposed norms of journalism. In the twentieth century, when news content was scarce, popular attention was high, and a small number of professional journalists had a monopoly on big stories, reporters policed themselves and felt responsible for spreading the truth. Today, news content is far more abundant than popular attention. The internet eliminated professional journalists as gatekeepers, and online outlets are free to disseminate information whether or not they have verified it.

American law also makes it difficult to combat fake news. The Supreme Court’s decision in New York Times v. Sullivan established a high bar for defamation lawsuits brought by public figures, and the Communications Decency Act provides legal immunity to technology platforms that circulate false stories. Though certain FCC and FTC regulations bar corporations from passing off sponsor messages as editorial or noncommercial speech, Goodman emphasized that those rules concern source identification rather than content, and prohibitions on false advertising do not extend beyond the commercial sphere. Free speech laws rest on the Enlightenment assumption that people can discern truth from falsehood for themselves.

Mr. Tucker examined propaganda through the lens of national security. He explained how ISIS caught the U.S. government flat-footed, appealing to disaffected young men worldwide through targeted social media campaigns and one-on-one communication with recruits. In 2014 and 2015, a third of the young caliphate’s civil servants were propagandists. The initial American response, a State Department campaign called “Think Again Turn Away,” involved approximately 25 U.S. government employees fighting 50,000-90,000 ISIS users across the internet. The content was almost entirely in English, and explicit government branding gave it the appearance of awkward public service announcements. Ultimately, the pseudo-jihadis made U.S. officials look foolish in Twitter wars, and an embarrassed administration took a new direction.

The State Department’s Global Engagement Center appears more effective than the Think Again Turn Away campaign. Led by Michael Lumpkin, the former Undersecretary of Defense for Special Operations, the Center gives grants to private organizations to research and conduct one-on-one marketing to populations from which ISIS recruits. It is difficult to measure the extent of the Center’s success because its efforts coincided with ISIS losing territory, which diminished the caliphate’s propaganda machine. Even with ISIS’s decline, Tucker stressed that other actors such as Russia will continue to use propaganda against the U.S. While foreign enemies see truth and falsehood in strategic terms, Tucker noted that Americans view a commitment to truth as “a key aspect of our identity.”

Stanley and Goodman attempted to identify non-governmental mechanisms for fighting propaganda. To counteract the threat of tyrants stoking popular fears, claiming the mantle of “protector,” and never relinquishing power, Stanley invoked Rousseau’s contention that democratic education systems must foster a “common information sphere,” encouraging citizens to engage, rather than resent, their fellows. Partisan echo chambers jeopardize democracy, so citizens need to “reconstruct civil society” by transcending their social bubbles (in other words, Yale faculty should try writing in the Dallas Morning News instead of The New York Times). “Good” propaganda could promote democracy by creating an “emotional attachment” to truth and liberal ideals. However, Stanley predicted that, like many forms of government that came before it, liberal democracy will not survive.

Goodman advocated investment in local media to counteract propaganda, noting that individuals on the ground have an easier time verifying information. She was skeptical of proposals to ask unregulated technology companies such as Facebook to police online platforms. These corporations need to be more transparent and accountable to the public, she said, so it would be helpful if computer scientists developed a professional ethical system analogous to that of twentieth-century journalists.

Panel 2: Information Warfare in the Cyber Era

Moderated by Professor Oona Hathaway

Speakers: Professor Catherine Lotrionte, Georgetown University; Jacquelyn Schneider, Naval War College; Dr. Aaron Brantly, United States Military Academy

The second panel focused on using propaganda as a weapon. Dr. Brantley analyzed Russia’s recent use of information warfare to facilitate its incursions into other states. In Afghanistan, the Russians portrayed themselves as communist saviors who would help bring the country into the modern world. They misunderstood their audience, never connecting with Afghans on an interpersonal or cultural level, and their failure helped doom the occupation. Russia was more effective in nearby Georgia and Ukraine, according to Brantley. It fueled divisions within Georgia by disseminating false, graphic images of local ethnic groups inflicting violence upon one another, creating a justification for Russian intervention. Just as the Western Ukrainian government eliminated Russian as a national language, Russia spread the falsehood that the regime supported Nazi Germany, cognitively priming Russian-speaking Ukrainians to support the annexation of Crimea. The cultural and linguistic similarities between Russians, Georgians, and Ukrainians made the propaganda all the more effective.

Representing U.S. Cyber Command on the record, Ms. Schneider explained how the Department of Defense (DOD) protects American cybersecurity. Historically, DOD focused on using information to create battlefield advantages, fight “network-centric” warfare, and plan military campaigns. Now, the Department recognizes the impact of information to influence events before wars begin and to derive economic advantage. DOD adheres to strict rules of engagement when engaging in offensive cyberwarfare, to include information operations. On the defensive side, Cyber Command protects national security and infrastructure information by fortifying cyber networks (“deterrence by denial”) and by reserving the capability to retaliate against technological attacks through conventional and cyber means (“deterrence by punishment”), according to Schneider. The White House exercises significant authority and oversight of these initiatives. Finally, Schneider highlighted the tension between America’s efforts to strengthen its cyber infrastructure with its belief in internet freedom. To an extent protecting the latter weakens the former, but the U.S. government believes that fundamentally a free internet reinforces American security.

Professor Lotrionte examined the international legal framework governing information operations and cyberwarfare. Regulated activities include espionage (“computer network exploitation”) and cyber incursions (“computer network attacks”). The U.S. government has pledged to operate in cyberspace according to global norms governing the initiation and conduct of warfare, recognizing that the destructive use of information could violate Article 2(4) of the UN charter, which could allow a country to invoke Article 51 and use force in self-defense. UN Security Council members Russia and China disagree about the extent to which the international law of armed conflict applies to cyber activity, and they clash with America over internet censorship. In short, the world’s great cyber powers are playing by different rules in cyberspace.

Brantly and Lotrionte debated what differentiates a cyberattack—which could justify military retaliation under international law—from mere “information warfare” and espionage. Specifically, while they agreed that the “coercive” use of propaganda could violate the customary international law prohibition on intervention in a sovereign state’s affairs, they disagreed regarding whether the Russian hack of the Democratic National Committee and Wikileaks’ subsequent dissemination of the information was a coercive act. Lotrionte contended that the hack coercively undermined the legitimacy of the U.S. election, while Brantly argued that the mere dissemination of DNC emails did not compel U.S. citizens to do anything. Unlike interfering with voting machines, Brantly claimed, the Russian effort left voters free to respond to the leak as they wished.

Professor Oona Hathaway concluded the conversation by reflecting on the national security paradoxes of the information age. Unprecedented access to data helps the U.S. spread messages across the world, but it creates vulnerability in our own systems. There is no easy answer to the question of how America should balance its liberal values and security interests. The Weaponizing Information Conference “air[ed] the messy mix of challenges” that U.S. policymakers face.

—James Mooney ’19