Bookbindings Tell A Story at the Law Library

A 17th-century volume of regulations for an 18th-century overseer of Rome’s prisons. An album of watercolors circa 1850 illustrating the “Punishments of China” for the tourist trade. A rare chained book from England circa 1620. A volume from 17th-century diarist John Evelyn’s library.

These are a few of the treasures currently on display at the Lillian Goldman Law Library exhibition “Legally Binding: Fine and Historic Bindings from the Yale Law Library” which sets out to purposefully judge books by their covers.

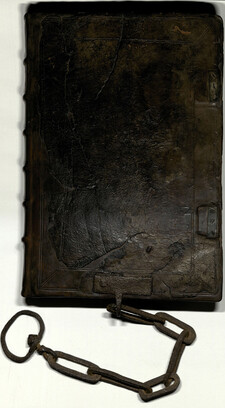

A rare chained binding from England ca. 1620.

The exhibition, curated by Rare Book Librarian Michael Widener and Michael Laird of Michael Laird Rare Books, gathers 34 volumes from the Yale Law Library’s Rare Book Collection, the latest in a series of exhibitions focusing on the book as object.

“I look for things that show evidence of use, previous ownership, and have stories to tell about the people who read it, owned, it and sold it,” said Widener.

In keeping with telling these stories, each item is labeled with information about who the book was for. Examples include a Mexican landowner and his attorneys, an Italian notary, an attorney or judge in the 16th century Venetian Republic, and a book for the British masses in the 19th century.

Bookbindings, Widener said, can tell us a wealth of information. “You see changes in material, whether the book was intended to be used in a private setting or be portable. Was it chained, or laid flat, was it meant to have its fore-edge facing outward instead of the spine.”

Bindings also help point out regional differences in book design and construction. Which way the clasps on a book are positioned or how it is decorated provide clues to its origin, if you know what to look for. And, over time, bookbindings show changes in construction, as the industrial age arrived and more products were produced by machine.

Ryan Martins ’20, the Rare Book Fellow at the Law Library, helped curate the exhibition. For him, the exhibition offers the opportunity to showcase rare books as a unique combination of content and medium.

“By exhibiting the books closed, we de-emphasize their content, and instead put the focus on their form,” he said. “This is especially important in an era of digitization, where the content of any given book may be readily available online. What cannot be digitized in a meaningful way is the leather, cloth, or vellum used to wrap a book, or the heavy iron clasps used to keep them closed, or even the glint of the gold which adorns many of our volumes. Yet these are an integral part of our understanding both of what a book is, and of how texts would have been experienced by people for generations before the advent of mass printing or digitization.”

Other highlights in the exhibition include:

- The ordinances of a mining guild in the Peruvian city of Arequipa, then one of the richest cities in the New World. Likely created for one of the mine owners, the binding is handmade velvet and the clasps made of silver that almost certainly came from Arequipa’s mines.

- The oldest binding in the Law Library’s collection remains completely unrestored from the late 14th century. Bound in deerskin over wooden boards and kept closed with a leather strap, it survives as an unsophisticated but extremely rare example of medieval bookbinding.

- A copy of the Constitution of the state of Massachusetts and that of the United States, circa 1805, that survives despite being bound in scaleboard, an inexpensive and fragile piece of thin wood. Owned by three brothers in the early 1800s, the heavily used school book’s survival to the 21st century is remarkable.

The exhibition is on view at the Lillian Goldman Law Library through May 24, 2019. It is also viewable online with explanatory text from the exhibition labels.