Exhibit on Alumna Shows a Life of “Perseverance and Resilience”

The wide-ranging career of Inez Smith Reid ’62 is shown in an exhibit at the Lillian Goldman Law Library, giving the trailblazing alumna an occasion to reflect upon her life during a recent visit.

The exhibit4 on Reid — judge, scholar, and presidential appointee — is the second installment of “A Celebration of Women at Yale Law School,” the library’s series of exhibits in advance of 50 Yale 1505, the university-wide program set for next year to mark the anniversaries of women’s enrollment in Yale College and the graduate schools.

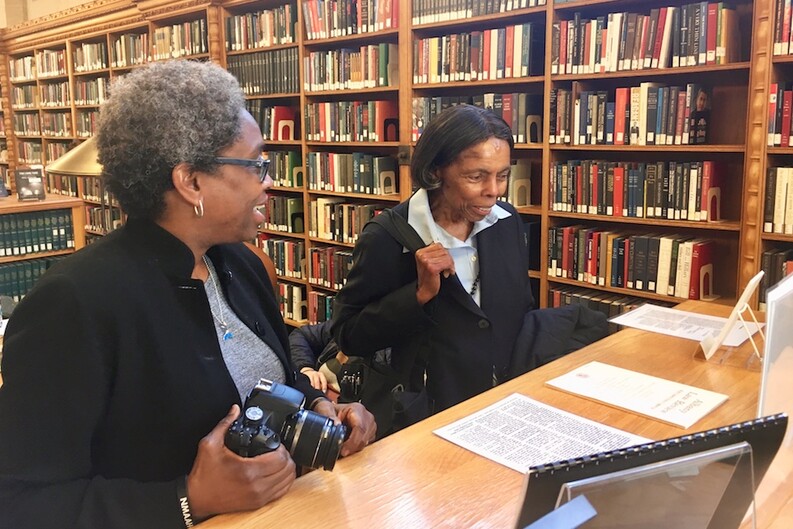

Returning to the Law School last month, Judge Reid walked along the display, which features about two dozen items from the library’s collection as well as her own, with exhibit co-curator Shana Jackson. Asked what came to mind when seeing the items, Reid said, “How fortunate I was to be able to do different things in life, all of which were very challenging. It brings back good memories.”

Born in New Orleans and raised in Washington, D.C., during segregation, Reid received an LL.B. from Yale Law School, where she and her twin brother, George Bundy Smith ’62, were the lone African American students in their class, and where, it has been said, they were often mistaken for staff. A 1959 Law School facebook photo shows a particularly young-looking Reid, then a recent graduate of Tufts University. Asked what she was thinking around the time of the photo, Reid said, “I was probably glad to get out in one piece.”

With many jobs in law closed to her, Reid pursued a career in academia. She earned an M.A. in political science from UCLA and a Ph.D. from Columbia. She then taught in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and later at several American universities, spending a decade in education before practicing law — happily, by her own account. At the urging of her brother, who challenged her to “justify” her law degree, she accepted the first of her many public appointments, starting in New York state government. In 1979, she became the first Inspector General of the Environmental Protection Agency, appointed by President Jimmy Carter. In 1995, she was nominated by President Bill Clinton as an associate judge on the D.C. Court of Appeals — the highest court for the District of Columbia — and sworn in by her brother.

Jordan Jefferson, co-curator of the exhibit, said the materials on display highlight not only Reid’s scholarship, but the breadth of her career.

“She was an educator, a judge, a public servant, and she worked for a private law firm as well,” Jefferson said. “She’s done pretty much everything you can do after law school.”

Viewing the exhibit, Reid started with the most recent photo, taken with former Yale Law School dean Guido Calabresi ’58 during a 2018 visit for the unveiling of a portrait of Pauli Murray ’656, whose time at the Law School overlapped with Reid’s. Calabresi, Reid’s torts professor, was “very good,” she said.

She also paused at a copy of her 1975 book “Together” Black Women, researched with the Black Women's Community Development Foundation, of which Reid was executive director. The book, a sweeping effort to compile the opinions of black women, is based on interviews with 200 activists around the country. Reid said the conversations encompassed their views “on politics, social life, social movements, a lot of their thoughts in historical context.” Jefferson called the book “an underrated classic.”

Looking at an interview from her time with the EPA with the provocative quote “I’m not a super cop,” Reid said, “I like this article. He did a nice job.” Responding to a remark that the article feels timely, given the current state of the EPA, she simply replied, “Right,” and chuckled softly.

Jackson said Reid’s soft-spoken response is characteristic. But this quiet demeanor contrasts with Reid’s writing. Jackson pointed to a remembrance Reid wrote about her brother in the Albany Law Review. In it, Reid matter-of-factly describes their experience growing up under segregation and quotes his graphic accounts of the violence he witnessed as a Freedom Rider in Alabama. Another article on display is entitled “Optimism is not Warranted: the Fate of Minorities and the Economically Poor Before the Burger Court.”

“You could see how feisty she was,” Jackson said. “She was willing to speak her mind.”

Asked what she hopes scholars will take away from her papers, Reid said, “The need for perseverance and resilience. Overcoming hurdles.”

Jackson gestured to another display7, a selection of films that depict black characters in professions in which black professionals are usually underrepresented. She said Reid is a real-life example of the same.

“She is truly a hidden figure,” Jackson said as students sitting a few feet away remained buried in their books.

Reid took in the scene, looking around the library. Asked what has changed since her time at the Law School, she said, “Not much.” She barely paused. “Well, the complexion of the students has changed. And they all seem pretty relaxed.”

Was that not the case in her time here? “No,” she said, smiling. “No, no, no. It was pretty intense.”

“A Celebration of Women at Yale Law School,” showcasing the life and career of Inez Smith Reid ’62, is on display at the Lillian Goldman Law Library’s Reading Room through April.