Human Rights Workshop: Repression and Resistance in Cuba

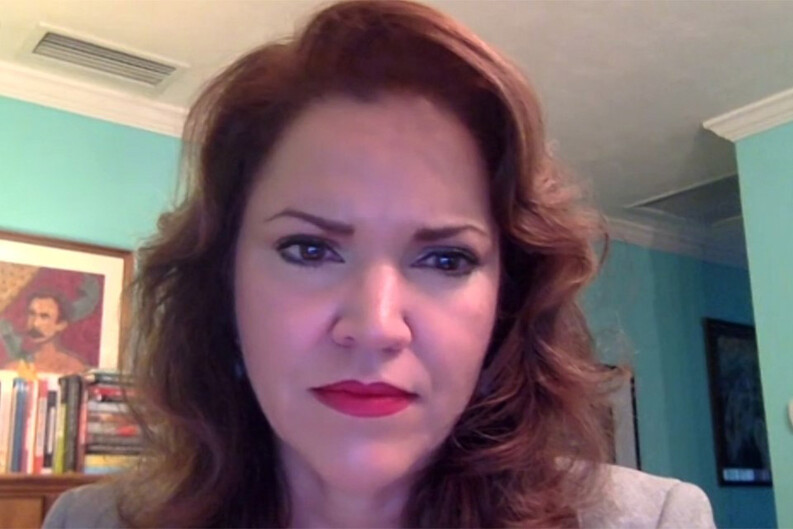

At the Sept. 17 Human Rights Workshop4, University of Florida Professor of Cuban and Caribbean History Lillian Guerra described the Cuban government’s sustained use of surveillance against its citizens and how that catalyzed the protests of July 11, 2021, the largest on the island in decades.

Guerra’s presentation, “Fighting for a Higher Law: Race, Class and the Bonds of Complicity in Cuba,” included an overview of the historical and legal precedents for repressing Cuban citizens’ freedom of expression in the 1960s and 1970s. Guerra also discussed the recent emergence of resistance in the forms of rap songs and protests.

On July 11, more than 200,000 Cubans “of all generations, colors, and backgrounds” protested a lack of freedom of expression and assembly, the Communist Party’s “monopoly on rule,” and the “absence of any legal right to protest it,” Guerra said. The prohibition on freedom of assembly, she noted, has existed since the 1970s. Today, she said, about 5,000 of the July 11 protesters — among them minors — are imprisoned and face trial. “Because, in Cuba, the primary responsibility of a lawyer is to defend the revolution, and because Cuba’s judicial system enjoys a 92 percent conviction rate, the outcome of such trials seems pre-determined,” Guerra added.

The demonstration began in the town of San Antonio and “spread like wildfire,” according to Guerra. Months earlier, rappers Descemer Bueno, Gente De Zona, and Yotuel spurred millions of Cubans to express dissent with the rap song “Patria y Vida,” which went viral on YouTube in February 2021.

“[The song] assaulted communist leaders’ claims to power and legitimacy on political, economic, and moral grounds,” Guerra explained. The lyrics, Guerra said, inspired quotes such as “your vision is 1959 and mine is 2021.” The musicians, according to Guerra, were raised in predominantly Black, disproportionately poor barrios in Havana, and their upbringing inspired some of their lyrics: “No more lies. The people ask for freedom not more indoctrination. We should not shout fatherland or death, but fatherland and life...Stop spilling the blood of those who want to think differently. Who told you Cuba was yours? Because Cuba belongs to all my people.”

The rap songs defy recent steps by the Cuban government to crack down on dissent, Guerra explained. In 2019, she said, a new constitution endowed the Communist party with the “unique right to embody the will of citizens.” Legal Decree 370, passed shortly after, made sharing information contrary to the public interest on social media a criminal offense. She noted that 2019 was also the first year Cubans were able to access the internet through their cell phones. The government also enforced Legal Decree 349, a “sweeping law” that reversed reforms in place since 1991, including those that allowed artists and intellectuals to publish, disseminate, and sell their work without government intervention. Guerra characterized this move as the creation of a “new category of political crimes” later labeled as “social media terrorism.”

Following the July 11 protests, Guerra suggested, the government seemed to decide that “these legal weapons were not enough.” The Council of State approved what Guerra described as “the two most draconian laws for the repression of political dissent and independent thought” passed in Cuba since the 1830s. On Aug. 17, the Ministry of Communications issued Resolution 125, which makes “all signs, signals, writings, images, sounds, or any information” aiding an individual or collective attempt to subvert the constitutional order as a form of terrorism. As a result, those who use Twitter, Facebook, or any other social media platform “on the pretense of altering the public order or promoting social indiscipline” commit the crime of “social political subversion.”

On the same day, Legal Decree 35 was passed. This decree criminalizes Cubans’ use of the internet or any other telecommunications service to “subvert national security by transmitting false news, offensive information, or content that affects the collective security, general welfare, public morality, and respect for order.” Strikingly, Guerra noted, this law makes both the user and the service provider equally liable for “politically dangerous or ideologically offensive content.”

Guerra explained how three artists who were arrested by state security prior to the July protests have been charged with violations of these two laws retroactively. The state charged the three artists with public disorder and instigating others to commit crimes, even though two of them were in custody during the July protests, she said.

Guerra also explained the historical significance of the public outrage in July, noting that it was driven by Black and African-descended Cubans. “The weapons they wielded were ideas,” she said. “Some expressed outrage over the government’s constant reliance on the U.S. embargo as an excuse to monopolize power and control the distribution of food.”

The demographics of the protest are significant, according to Guerra, because revealing evidence of anti-Black racism and poverty has been “political taboo” in Cuba since the early 1960s. Paralleling today’s censorship, she described how Black activists, artists, and intellectuals from the 1960s to the 1980s also faced censorship, unemployment, and hard manual labor disguised as “political rehabilitation” on state farms.

The government’s current strategy of defaming activists and artists as “morally-corrupted, socially-dangerous misfits” is nothing new, Guerra said. As early as 1960, for instance, Fidel Castro issued Law Decree 988 that punished providing water, food, information or moral support to opponents of the party with death or imprisonment for up to 30 years. Guerra also pointed to 1960s-era Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, which empowered ordinary citizens to surveil and sanction their neighbors for insufficient loyalty to the party.

Guerra sees July 11 as a turning point for the island and for the freedom of expression of Cubans. She concluded with the words of an elderly Black woman at the protest in front of the Capitol building that day: “We have spent more than 60 years amidst lies and deceptions. We are taking off the rags of silence.”