Launching Careers in Service

Yale Law School-funded fellowships offer essential support for aspiring public interest lawyers serving communities around the world.

Maya Menlo ’18 spent most of her time at the Washtenaw County Office of the Public Defender in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on the important but unglamorous tasks that keep the machine of justice running. Her main project for the year she spent there as a Liman Fellow was developing an arraignment defense unit, with the goal of ensuring all indigent clients in the county had legal representation during that vital early phase in their cases. It was a step-by-step effort that involved solving knotty technical challenges and deft navigation of bureaucracy.

But because the office was small and resources were tight, she also had a small client caseload of her own. “Something I’ve always enjoyed, and think is extremely important, is sentencing mitigation, and also mitigation that can be used to bargain for a better plea offer,” Menlo said. She fought hard for her clients, trying to secure the best deals possible.

In the summer of 2022, Menlo heard from a former client, a woman for whom she had negotiated a very strong plea offer. The woman was now out of jail, sober, and in school — “all the things you’d hope,” Menlo said — and wanted her attorney to know that the representation she’d received had changed her life.

“That was very, very memorable,” Menlo said. “You don’t always get those, you know?”

For alumni like Menlo who pursue careers in public interest law, the opportunity to help others and advance causes they care about is what keeps them in the field — and postgraduate fellowships are an essential first step in lighting up that career path. In fact, for many nonprofit organizations, hiring junior attorneys would be impossible without the funding fellowships provide. Getting one “is almost necessary if you want to do this type of work,” said Mollie Berkowitz ’21.

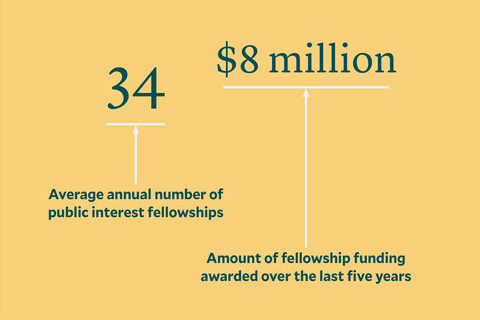

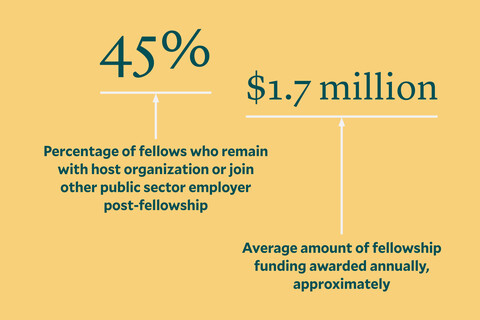

To help clear the path for aspiring public interest lawyers, Yale Law School funds significantly more postgraduate fellowships per student than any other law school in the country — an average of 34 per year. Menlo remembered hearing at the Admitted Students Program “just how many fellowships per capita there were.” For her, “that was probably the deciding factor in coming to YLS.” And the nearly $2 million in annual fellowship funding benefits both students and the organizations they serve.

Serving students and the legal profession

Dean Heather K. Gerken described the Law School’s model of funding public interest fellowships as essential to the school’s mission and the values of the legal profession. “We take great pride in supporting graduates who devote their careers to giving back and positively impacting the lives of the most vulnerable and marginalized members of our society,” Gerken said.

The Law School, she said, has long outpaced its peers in supporting public interest work. “We support this critical work so that resource-starved nonprofits can hire passionate law graduates through Yale-funded fellowships,” she said. “These positions help improve communities and deal with some of the most pressing issues of our time.”

To receive the competitive fellowships, applicants — who can be students or alumni — generally find a sponsoring organization, then apply to receive funding from Yale Law School or outside groups. These include the Skadden Fellowship Foundation and Equal Justice Works, as well as Yale’s own fellowships: the Arthur Liman Public Interest Fellowship, the Gruber Fellowship in Global Justice and Women’s Rights, the Heyman Federal Public Service Fellowship, the International Court of Justice Fellowship, the Mary A. McCarthy Fellowship in Public Interest Law, the David Nierenberg ’78 International Refugee Assistance Project Fellowship, the Robert L. Bernstein Fellowship in International Human Rights, the Robina Foundation Human Rights Fellowship, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague Fellowship, the YLS Public Interest Fellowship, and the Yale Law Journal Fellowship.

A valuable first step

Alumni say their fellowships provided formative support and invaluable resources needed to begin public interest careers. “There’s definitely an emphasis on fellowships and pursuing the public interest at Yale,” said 2017–18 Gruber Fellow Zain Rizvi ’17. The availability of fellowships, clinics, and practicums meant that “every student could chart their own path,” added 2014–15 Bernstein Fellow Kyle Delbyck ’14.

For some, fellowships are the start of a lasting relationship — from the most recent responses to the Yale Law School post-fellowship employment survey, 42% of fellowship recipients received offers to remain at their host organizations. That was the case for Berkowitz, who started as a Gruber Fellow at the legal advocacy nonprofit Public Justice and stayed for a second year, before beginning a clerkship in 2024. “I’m so grateful to be able to continue the projects that I’ve been working on over the last year,” she said.

Berkowitz first learned about Public Justice through Alexandra Brodsky ’16, a staff attorney at the organization and a visiting lecturer at the Law School; Berkowitz also served as a research assistant for Brodsky’s book Sexual Justice: Supporting Victims, Ensuring Due Process, and Resisting the Conservative Backlash. Thanks to this collaboration, Brodsky knew that Berkowitz had an interest in cases related to sex and race discrimination in schools and encouraged her to pursue a fellowship with Public Justice.

Working with Public Justice has also allowed Berkowitz to focus on litigation — a distinctive aspect of the organization’s program that appealed to her. “A lot of fellowships tend to be more policy-focused, because many organizations, though not all, farm out litigation to the pro bono arms of big law firms, and Public Justice doesn’t do that,” Berkowitz explained.

Her day-to-day tasks involved researching memos, drafting briefs, preparing for appellate arguments, conducting intake with potential clients, and collaborating with non-lawyer advocates working on sexual and race discrimination issues. She’s had some early tastes of success, including “an absolute slam-dunk opinion” in the case where she briefed her first motion for summary judgement.

Berkowitz said the work feels especially meaningful at a time when the rights of victims of sexual harassment and assault and the rights of members of the LGBTQ+ community are under threat. Despite these challenges, “I’m proud to say that, by and large, in our cases, we’ve been getting good results,” she said — and she has no intention of letting up. “It just feels like it’s the only way. I can’t imagine doing any other type of work while this is happening in the wider world and in the judiciary.”

Menlo, too, continues to feel called to the work she began during her fellowship. She’s still doing defense work in Michigan, her home state, now with the State Appellate Defender Office. And the arraignment defense unit she helped establish at the Washtenaw County Office of the Public Defender — the state’s first — is still going strong. In fact, she learned that other public defender offices in Michigan used Washtenaw County’s approach as something of a model.

“I do feel like we got it done,” she said. “By the time I left, there was a fully functioning arraignment unit where everybody who was indigent and needed an attorney at arraignment got one” — no small feat.

Serving the public, at home and abroad

While Berkowitz and Menlo used their fellowships to address domestic challenges, other alumni, including Rizvi and Delbyck, opt to work internationally. Rizvi, who is now senior health counsel for the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, spent his fellowship at SECTION27, a human rights organization in South Africa, where he focused on issues surrounding access to medicine.

The fellowships were the fulfillment of many years of planning. Rizvi became interested in global health as an undergraduate and saw law as the best way to address the issues he studied. “I came to Yale with a very specific interest,” he said. “Even my personal statement was very much focused on the injustice of the current intellectual property system and how that impeded access to medicine for people around the world.” His faculty mentors at the Global Health Justice Partnership at the Law School — Amy Kapczynski ’03, Gregg Gonsalves, and Alice M. Miller — knew of SECTION27’s work and suggested Rizvi pursue a fellowship there.

For Rizvi, the opportunity to work in South Africa was particularly exciting because of its long history of activism and advocacy around medication access. In the early 2000s, the country was at the center of an effort to challenge intellectual property monopolies that made HIV/AIDS drugs prohibitively expensive. “South Africa now has the largest HIV/AIDS treatment program in the world, and many HIV medicines are available and accessible now in a way that they weren’t previously,” he said. “The reason I wanted to go to law school was to build on that — to take the baton and run with it.”

South Africa has undertaken a broader intellectual property reform process. At SECTION27, Rizvi focused his work on studying how such changes might affect the accessibility of other types of medicines — in particular, cancer drugs, many of which are not widely available in the country because of their prices.

“I did a lot of analysis like that, but the best part of my fellowship was that it wasn’t just analysis,” Rizvi said. “I was deep in the weeds on patent law, but I also was marching with the grassroots communities, demanding access to better care…For me, it was a transformative experience to learn from some of the world’s leading advocates.”

Like Rizvi, Delbyck arrived at Yale Law School with a clear ambition. Before starting law school, she’d received a fellowship that allowed her to explore her growing interest in transitional justice — the ways in which countries respond to serious human rights violations. Her travels took her to Cambodia, Bosnia, Argentina, and Taiwan. Along the way, she said, “I decided to apply to law school, and my focus throughout was international criminal law and war crimes tribunals.”

Delbyck spent the bulk of her fellowship in Sarajevo working with TRIAL International, a global organization that assists victims of conflict. She’d previously done an internship with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia; that experience introduced her to the work of domestic war crimes courts, which she came to view as “the next frontier for war crimes proceedings. Before, a lot of the proceedings had been through international mechanisms.” Bosnia was one of several countries trying to develop an effective internal system.

But Bosnia’s courts, like those of many countries, were burdened by biases — particularly when it came to victims of wartime sexual violence. “The gender biases and stereotypes that emerged around these trials often resulted in acquittal or in the survivors not getting compensation,” Delbyck explained. Victims’ sexual histories or failures to fight back physically were held against them, even when they were assaulted in contexts such as detention camps, where they clearly could not give consent.

One of Delbyck’s fellowship projects involved developing a report on how to prevent gender-based stereotypes from influencing legal proceedings. “That report eventually got incorporated into the training program for judges, which is very rewarding,” she said. Another, in collaboration with Yale Law School’s Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic, involved advocating against burdensome statutes of limitation that prevented wartime victims from obtaining justice.

Delbyck said her work today, as senior program manager at the Clooney Foundation for Justice’s TrialWatch initiative, is a direct outgrowth of her fellowship. The time she spent talking to judges, attorneys, and victims “gave me a very nuanced sense of how trials proceed” that “paved the way for me to do this more intensive work in trial monitoring in my position now.”

Lasting impact

Rizvi and Menlo, too, feel their fellowships provided preparation and support they could not have gotten otherwise. For Menlo, who chose Yale Law School because of its public interest fellowship offerings, the school “returned on the promise,” she said. “Getting back to Michigan and having a paying job where I was going to be doing something interesting and important at an agency I cared about and wanted to be at was everything…That first stop on the train of my career was extremely important.”

Rizvi said his time as a fellow continues to propel his work. “It really helped me understand in a deeper way how these arcane areas of law can have a profound impact on public health,” he said. “Once you see it, you can’t look away from it.” He’s grateful his first job out of law school allowed him “day in and day out to sit and think about how to make the world a better place. That was an incredible privilege, and I recognize that every day.”