Leilani Farha Confronts the Commodification of Housing

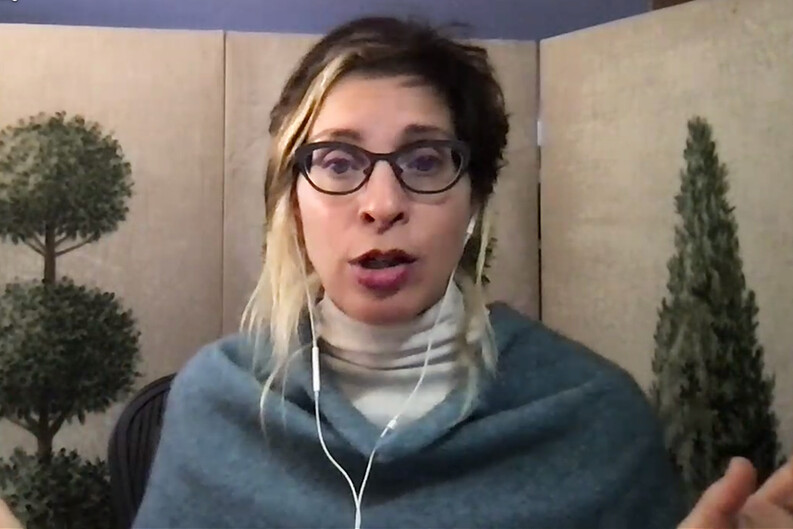

Leilani Farha spoke at the Feb. 10 Human Rights Workshop on the financialization of housing and the international movement to secure the human right to housing. The Global Director of The Shift and the former U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, Farha is the protagonist in the award-winning film PUSH, which documents her work on finance, housing, and human rights.

“There’s a lot of people making a lot of money off of housing, and it’s creating homelessness,” Farha said, “How has it become the reality that the richer a nation is the more likely you are to see escalating rates of homelessness? Everyone should be benefitting from the wealth of a nation, but that doesn’t happen.”

At the event, “Profit Grab: When Housing Creates Homelessness,” Farha shared statistics revealing the depth of the global housing crisis.

“1.8 billion represents the number of people living in grossly inadequate housing around the world, people who can’t afford a decent or adequate place to live, and who are already marginalized — often they are racial minorities, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, single parents, women, refugees and migrants, to name just a few,” she explained.

People in inadequate housing, according to Farha, often live without toilets, showers, and running water. The second number, 220 trillion, represents the “global value of [residential] real estate,” Farha said. “It’s the relationship between those two numbers that interests me.”

To Farha, the crisis originates in misguided and damaging economic policy.

“Neoliberal stalwarts imposed a now known-to-be-erroneous notion that if you just deregulate, take away tenant protections, remove the government from social housing, things will run smoother, more housing will be built, it’ll all trickle down, and benefit everybody,” Farha said. “But trickle-down economics has been debunked … it is neoliberalism that has allowed the likes of Blackstone to do what it has done in the area of housing.”

Blackstone, Farha explained, is one of the world’s largest private equity firms. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Blackstone “went on a shopping spree” in which they bought more than 50,000 foreclosed homes from banks. These purchases, according to Farha, “contributed to destroying the lives of already destroyed families … They created high-cost rentals, made a killing, and then removed themselves from the equation with lots more zeroes in their bank accounts.”

Blackstone and other private equity firms are essentially “preying on affordable housing,” she said. More recently, according to Farha, Blackstone set its sights on affordable housing in San Diego, in the midst of the pandemic. Of concern is that Blackstone may flip these affordable homes into market units, she explained, rendering them unaffordable.

“These are low-income, racialized people who may soon see their homes taken away from them,” Farha said. “Those homes are likely to be flipped to market rents … Blackstone has said they won’t do that, but that’s also what they said when they bought social housing in Spain, which they converted to market-rate housing.”

Farha emphasized that the government “does a lot to prop up actors in the neoliberal system.” She said tax advantages given to property owners, including the lack of taxes on real estate investment, mean, as Peter S. Goodman said in his new book Davos Man, “this is no longer capitalism … this is welfare for billionaires.”

Beyond economic power, institutional financial actors have substantial political power, according to Farha. For example, BlackRock, the world’s largest investment management firm, controls at least five percent of the shares for 97.5 percent of the top 500 publicly traded companies in the United States.

“They have a finger in every pie,” Farha said, “so they run the world because they own it all.”

She contended that BlackRock and other firms are “advising governments and stymieing legislative reform” and helping to “set interest rates” that benefit themselves.

“Is that who you want advising your government on policy that will impact how low-income people will be surviving the pandemic?” Farha asked.

She argued that the people most impacted by decisions around the selling of property and land and the setting of interest rates are the ones who should be deciding what happens. “Tenants and those living in homelessness should absolutely have a seat at the political table, at the local and national levels,” she said.

Farha expressed her strong belief in human rights as an “antidote” to these injustices. “Human rights is not just a rallying cry,” she said.

Governments around the world have ratified international human rights treaties and thus made commitments to protect certain rights under international law.

“Though the government of the U.S. hasn’t ratified all or many of the instrumental ones, it has ratified important ones on civil and political rights and racial discrimination — and in the U.S. all of the effects of the financialization of housing are absolutely discriminatory based on race,” Farha said. Institutional investors know, argued Farha, that racialized individuals are most likely to live in the “undervalued” assets that they make unaffordable by acquiring and then flipping them for profit.

Human rights is an “accountability mechanism” and it can be used to hold states accountable to their obligations to regulate actors like Blackstone and BlackRock and to secure the right to housing, Farha said.

“The threat of homelessness is a security-of-the-person issue, a right-to-life issue. What happens to homeless people can constitute cruel and inhumane treatment,” she said. “The domain of human rights and legal obligations that should trigger a wholly different approach to housing. It’s a wake-up call to governments that they can’t allow these actors to run amok.”

The Human Rights Workshop is a weekly series of the Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights.