Liman Center and Coalition Lessen the Harm of Connecticut’s Incarceration Lien Law

In 1995, Connecticut adopted a law that imposed a per-day fee on people for their time in jail and prison. Critics called the law “pay to stay” and have sought to repeal it, saying the law saddles formerly incarcerated individuals with insurmountable debt that limits their prospects after release. This July, thanks to efforts by the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law and its community partners, that law will change.

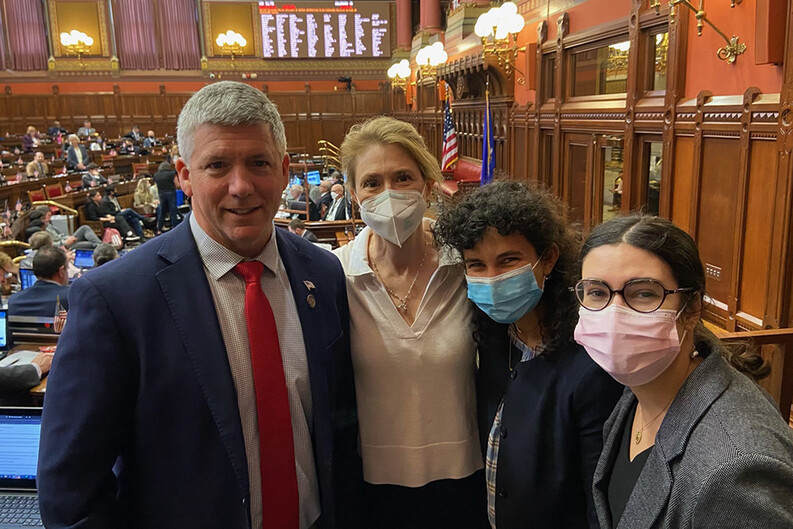

Liman Director Jenny Carroll and students in the Center’s pay-to-stay project worked over the past year to repeal Connecticut’s incarceration lien law through House Bill 5390. Although that bill did not pass, the 2023 state budget bill incorporated some of its language, with amendments. Governor Ned Lamont signed the budget bill into law on May 9.

“While our coalition was disappointed that the legislature did not fully repeal the incarceration lien this year, we do believe that the changes adopted will significantly curtail the impact of the lien by limiting those it affects, property it can attach to, and the length of the lien,” Carroll said. “It is an improvement that will provide economic security and better re-entry prospects for some of our state’s most vulnerable people.”

Under the current law, the state can claim lawsuit proceeds, inheritances, and lottery winnings for up to 20 years after someone is released from jail or prison. Under the new law, starting July 1, an incarcerated person’s first $50,000 of property is exempt from the lien. Any claim on this property must be brought within two years of the individual’s death or release from custody. In addition, the lien will no longer apply to civil settlements. However, the state can still take money from inheritances. These changes apply to people while they are serving time and after they have served time, with two exceptions. The $50,000 exemption does not apply to people who have been convicted of designated felonies. The exemption for civil settlements also does not apply to those who have been convicted of designated felonies.

Changes to the law are a direct product of the hard work of students Mila Reed-Guevara ’23, Ryanne Bamieh ’23, Ann Sarnak ’23, Danny Li ’22, and the community coalition, Carroll said. Students conducted research, presented their research at a press conference, and helped prepare testimony for public hearings. They did this work in collaboration with legal academics, community members, advocacy groups, and students from Quinnipiac University and the University of Connecticut School of Law.

Carroll, who will step down as Director at the end of May to return to full-time teaching, said the pay-to-stay project has been among her most significant work at the Liman Center.

“The students did a great job thinking about different and creative ways to approach the problem while keeping the voices of those affected by the lien front and center,” she said.

To make the harms of the law concrete, students interviewed people who lost their money to the state as they tried to put their lives together. Students then helped make a short film featuring these interviews. They also, with Carroll, co-authored a commentary that cites some of these stories. In one story, a man was forced to turn over an inheritance that he would have used to start a business.

WATCH: Repeal the Connecticut Incarceration Lien

Like many of Liman Center’s reform efforts, the project is ongoing.

“Our coalition and our students are committed to seeing this repeal through,” Carroll said. “They continue to collaborate with legislative and community stakeholders to end this injustice.”

Liman Projects offer Yale Law School students an opportunity to collaborate on research to generate reform in criminal and civil legal systems. These projects are a component of the Liman Center, which promotes access to justice and the fair treatment of individuals and groups seeking to use legal systems.