In the News, Courts, and Classrooms, Attention Turns to Federal Indian Law

When Lexie Holden ’25 was choosing a law school, she had two non-negotiables: a thriving Native American student organization and opportunities to study and put into practice federal Indian law.

She found both at Yale Law School, where she is now a member of the Native American Law Student Association and took introduction to federal Indian law in her first year.

“Knowing that Yale Law School offered multiple federal Indian law courses, as well as clinics where such knowledge would be relevant, made the decision to attend YLS even easier,” Holden said.

In recent years, the Law School has expanded its offerings federal Indian Law beyond an introductory course to include an advanced course and clinic. These additions reflect students’ growing and sometimes personal interest in the subject. And the courses reflect the relevance of a topic that cuts across nearly every area of law.

Federal Indian law is the body of law from the U.S. government — treaties, statutes, executive orders, court decisions, and policies — that regulates and influences the activities of Native American tribes and their members. It is distinct from tribal law, the laws that individual tribal nations use to govern themselves.

Growing Interest

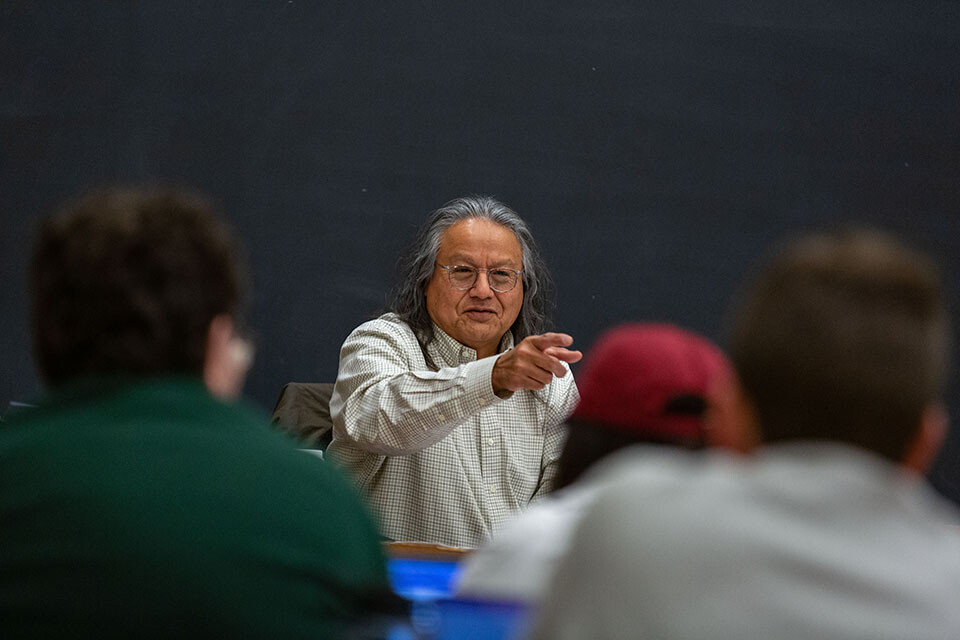

Professor of Law Gerald Torres ’77 started teaching an overview of federal Indian law when he joined the Law School faculty in 2019. In the introductory course’s early years, he would sometimes have a few students in class. These days, he said, enrollment can go as high as 50.

Torres believes that interest in federal Indian law has grown among students due in part to Indian nations becoming more politically powerful. The topic also draws students for the ways in which Indian law issues highlight the tensions in our constitutional system.

“Students want to understand the dynamics of power and how it is mediated by law, and few places illustrate that better than federal Indian law,” Torres said.

Issues of resource development and management on Native American lands have also driven attention to the topic, Torres said. At the same time, he added, increased attention to the free exercise of religion has sparked interest in how Native religions and sacred sites are protected.

The legal profession has taken note as well. Visiting Lecturer in Law Stephen Pevar, who taught Advanced Federal Indian Law last fall, pointed out that most of the 35 states with Indian reservations are home to firms large and small with lawyers who specialize in representing Native American tribes.

“It’s become very important for major law firms and our society to have familiarity with federal Indian law,” Pevar said.

Corporate lawyers who interact with tribal-run businesses must draft contracts with the knowledge that Native American tribes, as sovereign nations, are immune from civil lawsuits. Specific tax laws also apply. Criminal law practitioners must be aware of jurisdictional issues when crimes are committed on tribal lands. Land use attorneys encounter mineral and water rights principles that are unique to Indian reservations.

“Federal Indian law is no longer isolated to Indian reservations but has impact throughout our society.”

— Visiting Lecturer in Law Stephen Pevar

Cases involving federal Indian law are frequently before courts. One paper calculated4 that the Supreme Court has heard an average of 2.6 Indian law cases each term since 1959. On June 15, the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act5, which governs the foster care and adoption of Native American children. Pevar called the ruling “the most important federal Indian Law decision in a century.” Had the court overturned the law, Pevar explained, the ruling would have cast doubt on the validity of hundreds of laws involving Native Americans and their tribes. Changes to the 1978 law had the potential to affect thousands of families.

“Federal Indian law is no longer isolated to Indian reservations but has impact throughout our society,” Pevar said, adding that more than half of Native Americans live outside of reservations.

Legal education is catching up. Pevar noted that, when he started practicing in the 1970s, only one law school offered a course in federal Indian law. Now, federal Indian law is taught at roughly one quarter of accredited law schools in the U.S., according to a 2021 report by the National Native American Bar Association6.

Not Only an Academic Subject

For the increasing number of Native American students at Yale Law School, reasons for studying federal Indian law are often personal.

Kyle Ranieri ’24 is a member of the Navajo Nation whose family comes from the New Mexico side of the Navajo reservation. Before law school, he worked in business management consulting. Now he plans to pursue a legal career focused on tribal communities.

“Seeing the way that the [Navajo] Nation has interacted with law and the federal government inspired me to practice federal Indian law in order to support my community and all the communities across Indian Country,” Ranieri said.

K.N. McCleary ’24 is a first-generation descendent of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana. They said the issues covered in class — in particular, tribal water rights and the jurisdictional challenges that arise when indigenous people are murdered or missing — are not theoretical for some.

“As a Native student, I’ve seen the impacts these legal issues have had and continue to have on my communities, and I’ve so appreciated the opportunity to study them in depth and discuss them with my peers,” McCleary said.

Learning the Principles Behind the Practices

Some students in Torres’s introductory course came to law school after doing policy and advocacy work on Native issues.

Holden, a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, worked for organizations focusing on food and agriculture law and policy in Indian Country prior to law school. She said that understanding settled law and how courts interpret the law is important to her future work and will make her a more effective advocate.

“It’s one thing to draft policy which will have a positive impact on tribal communities,” Holden said. “It’s another to accomplish that while also minimizing the likelihood that the policy comes under scrutiny by the courts in the future.”

Ashlee Fox ’25 worked in the Office of the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, her tribal community, before law school. Her responsibilities there included the nation’s self-government compacts and funding agreements with the United States.

“I saw sovereignty in action, and I learned how federal Indian law and policy work in practice,” Fox said. “At YLS, I am learning the doctrinal principles that underlie the practices of tribal governance and tribal sovereignty.”

A “Vexed Area of Law”

In his introductory course, Torres traces current issues to the Marshall Trilogy, a group of 19th-century cases that form much of the basis of modern-day federal Indian law.

A question at the heart of Torres’ course is how the U.S. reconciles being a constitutional republic while maintaining a system that continues to function as a colonial system with regard to Native Americans.

“In addition to teaching the blackletter law, such as it is, my class has always focused on the justifications for the distribution of power in this vexed area of law,” he said.

Torres, who advised the U.S. Attorney General on Indian affairs while with the Department of Justice in the 1990s, said he wants students to gain an appreciation for the complexity of the legal problems that Indian law presents.

“I also hope that they see the clear limitations of the law in resolving the deeply rooted problems that relations with tribal nations force courts to confront,” he said. “Few courses expose the limits of judicial reasoning in the way that Indian law does.”

Torres said one of the advantages of Yale’s growing Indian law offerings is that he can design the introductory course knowing that it won’t be students’ only exposure to the issues. He now tailors the course to prepare them for advanced studies or clinical work. Recently, he taught the Saginaw-Chippewa Disenrollment Clinic, which pursued a claim against the federal government on behalf of disenrolled members of the Saginaw-Chippewa tribe of Michigan.

Pevar’s advanced course addresses contemporary issues like climate change, tribal sovereignty, the prevalence of violence against Native women, tribal jurisdiction over non-Indians, and the federal government’s trust responsibility. A guest expert joins the second half of each meeting to further the discussion.

“We were encouraged [in the advanced course] to propose solutions and ideas and really discuss them with our classmates, as opposed to just giving our opinions and moving on to the next topic,” McCleary said. “I found this to be a valuable experience and it helped me to think more critically about the issues facing Native nations.”

A Foundation for Future Decision-Makers

Torres hopes that students encountering federal Indian law for the first time will share the excitement that comes with studying a complex area of law. He said students will confront a difficult history and wrestle with the law’s role in justifying the policies affecting Native people.

“By having to grapple with the Herculean efforts that have been made to view Indian law as doctrinally coherent, they are forced to come to their own conclusions about the extent to which those efforts have been successful.” Torres said.

Students are already taking lessons learned in the classroom out into the world.

McCleary worked for their tribe’s Office of the Attorney General last summer. As an intern, they assisted in interpreting provisions of statutes impacting the nation, preparing memos on model tribal policies, and researching federal grant opportunities.

“I’m grateful for the foundation that Federal Indian Law and Advanced Federal Indian Law provided me,” McCleary said.

Outside of the Law School, students have worked with the NYU-Yale American Indian Sovereignty Project, a project of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Yale University and the NYU School of Law. Through the project, students have researched, among other issues, the impact of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta. The case concerns jurisdiction over crimes on Native lands.

“Working with the Sovereignty Project has enabled me to put all of the lessons I’ve learned into practice by being involved with some of the most pressing issues in federal Indian law before the Supreme Court,” Ranieri said.

Fox, who plans to be a litigator and serve her tribal community, has also thought about her fellow students who will pursue careers in other areas of law. She believes federal Indian law is critical for them to understand.

“YLS students will go on to become judges, government officials, and leaders across a number of fields,” Fox said. “It is essential that students understand fundamental concepts like tribal sovereignty and the trust and treaty responsibility because they will one day be decision-makers who will have an outsized impact — whether they realize it or not — on tribal nations and Native people.