Protecting Veterans

Students in the Veterans Legal Services Clinic Advocate for Their Clients’ Collective Needs in Court and in the State and National Capitals

When the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in 2017 that a lower veteran-specific appellate court could certify a class action or adopt another mechanism for hearing aggregate claims, the decision reversed decades of precedent and paved the way for veterans who have been denied benefits to pursue their cases collectively.

There’s a simple reason that such a decision didn’t come sooner, according to William O. Douglas Clinical Professor of Law Michael J. Wishnie ’93, director of the Veterans Legal Services Clinic, which filed the underlying case.

“Apparently no one had appealed,” he said.

That’s not so surprising in an area of the law that has long been under-resourced and segregated from mainstream civil rights and legal services practices. Wishnie started Yale’s veterans’ clinic in 2010 in part because most legal aid organizations don’t work on behalf of veterans, almost no organization has pursued strategic litigation for veterans since the 1970s, and veterans’ organizations who assist former service members generally assign only non-attorneys to represent them.

“There was a real siloing of veterans’ law even though it’s kind of classic poverty law,” he said. “And the lack of civil rights litigation has not benefited veterans — especially veterans of color; veterans with disabilities; and women, LGBTQ, and immigrant veterans.”

At the Veterans Legal Services Clinic, focusing on these marginalized veteran populations and thinking strategically with them about how best to address their legal problems is what students do.

That kind of thinking led to the landmark ruling that the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims (CAVC) could hear class claims and that court’s subsequent 2018 decision — which the then chief judge called a “seismic shift” — that it would.

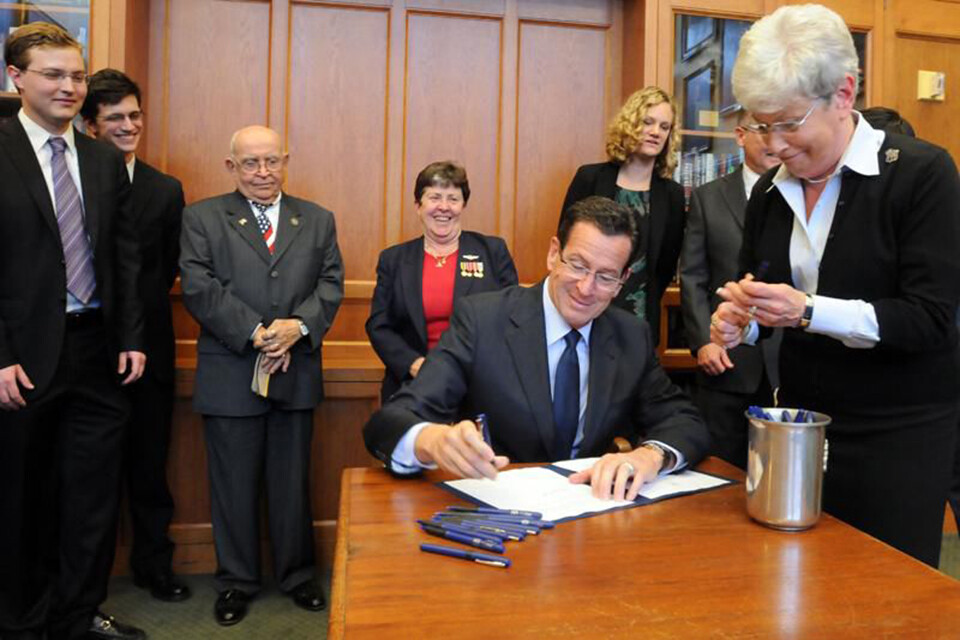

In other clinic matters, that strategic thinking has led to nationwide class action litigation and settlements that ensure tens of thousands of Iraq and Afghanistan-era veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), or military sexual trauma (MST) can have their less-than-fully honorable discharges reconsidered. And it has led to a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice recognizing that a decades-old law making it a felony for service members to join a union does not apply to National Guard members on state orders. It has also led clinic students to draft and successfully advocate for first-in-the-nation state laws in Connecticut as well as important new federal statutes.

“We focus on solving our client’s problems; if we can get to the resolution our clients are seeking, we are glad to use litigation, legislative advocacy, or any other number of lawyering tools to get there,” said Meghan E. Brooks ’19, who was in the clinic as a student and now works as its Robert M. Cover Clinical Teaching Fellow. “We tend to attack advocacy problems from all angles.”

Power in Numbers

The CAVC class action began, as many of the clinic’s matters do, with an individual client. Marine Corps veteran Conley Monk Jr., who served in the Vietnam War, had been applying unsuccessfully for VA benefits for decades. After filing again with the clinic, he waited years for a decision on his appeal of a denial of disability benefits. And he wasn’t alone. Several other clinic clients, and hundreds of thousands of disabled veterans, were waiting years as well.

“We have a practice called the ‘Rule of Three’ in the clinic,” Wishnie said. “If we see the same problem three times in our cases, we ask, ‘Is there something systemic going on here? And if so, is there anything lawyers like us could do about it?’”

For clients like Monk, who generally do not have attorneys, the clinic’s strategy had been to petition for a writ of mandamus in the CAVC. The court would order the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to respond within 30 days. The VA’s strategy was to wait 29 days and then issue a decision, thereby mooting the lawsuit. Although that process resolves an individual veteran’s case, the broader issue of lengthy delays goes unaddressed.

Monk was a longtime advocate for other veterans: He and his brother Garry Monk co-founded the National Veterans Council for Legal Redress. Conley Monk hoped to address egregious VA delays not only in his case but also in the cases of hundreds of thousands of other veterans. With Monk’s encouragement, the clinic decided to try something new. They filed a writ of mandamus, but they also added allegations on behalf of a class of similarly situated people who had been waiting more than a year to have their benefits appeals resolved. When the CAVC rejected the class claims, the clinic appealed.

“That’s what no one else had done before,” Wishnie said.

There was such a morally clear answer, and it was about how do we use the law to get to that point.”

—Catherine McCarthy ’19

The gambit paid off. John Giammatteo ’17 and Julia Shu ’16 argued the appeal, and at the Federal Circuit, the U.S. Department of Justice acknowledged that there was nothing stopping the CAVC from hearing claims collectively. The court agreed. On remand, Catherine McCarthy ’19 and Jordan Goldberg ’19, together with new co-counsel Lynn Neuner ’92 of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, then argued before the full CAVC, which had decided to hear the matter en banc.

The court ultimately issued a ruling adopting class action procedures.

“I want to emphasize the significance of the Court’s decision and the historic nature of this case,” wrote then-Chief Judge Robert N. Davis, who is now a senior judge and was the George W. and Sadella D. Crawford Visiting Lecturer in Law this fall, in a concurring opinion. “[T]he Court holds that it will, in appropriate cases, entertain class actions. This holding is a seismic shift in our precedent, departing from nearly 30 years of this Court’s case law… . [T]his is a watershed decision [that] will shape our jurisprudence for years to come and, I hope, bring about positive change for our Nation’s veterans and ensure that justice is done more efficiently and timely.”

Although the court divided 4–4 as to whether to certify Monk’s specific proposed class, the decision led the CAVC to promulgate new rules governing class actions. It has since certified four classes.

“We believe it is the first federal or state appellate court in the country to do so,” said Wishnie.

The significance of the Monk case is far reaching.

“The veterans’ space remains fairly under-lawyered,” Brooks said, so “the ability to pursue a class action is a way for clients to lift others up along with them.”

The strategy isn’t always entirely successful. After the government appealed a CAVC decision in another clinic case certifying a class of veterans who were deployed in the 1960s to clean up a radioactive site in Palomares, Spain, Caroline Markowitz ’23 argued in favor of keeping the class intact at the Federal Circuit last spring. But, this fall, the Federal Circuit issued a decision narrowing the class to only Palomares veterans who had exhausted their administrative claims.

Despite that setback, in part because of the clinic’s simultaneous legislative efforts, Palomares veterans with certain conditions are now automatically eligible for benefits. Over the years, clinic students advocated for that outcome, helping write and lobby for legislation, sponsored by Sen. Richard Blumenthal ’73, that was included in the PACT Act signed by President Biden in August.

Fighting “Bad Paper”

The CAVC reviews decisions by the VA regarding veterans’ benefits, but review boards in each branch of the military make decisions regarding a veteran’s discharge status, which can determine whether a veteran is eligible for benefits in the first place. The clinic has been battling on this front too, reviving the use of U.S. district court class actions against the U.S. Department of Defense for veterans — from the Vietnam-era and after — who received less-than-honorable discharges (called “bad paper”), often due to PTSD, TBI, or MST. Veterans with bad paper face widespread discrimination and stigma, and they are generally ineligible for VA benefits.

Jonathan Petkun ’19, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, worked on cases in that context against the Army and Navy. He also worked with the Connecticut chapter of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America to pass a state law extending benefits to Connecticut veterans even if they do have less-than-honorable discharges. Connecticut is the first state to take that step; New York later adopted similar legislation.

For Petkun, the cases and legislation have added significance. Part of his job as an officer in the Marines was to discipline his soldiers for misconduct, including with less-than-honorable discharges.

“I did everything by the book, the way I was trained to do,” he said. “But, when I was in the service, I always told myself, if these folks have been treated unfairly, there’s got to be some sort of backstop, some redress if they’ve been wronged.”

In the clinic, Petkun realized that the backstops — the discharge review boards — “weren’t working quite so well as I thought.”

As a result of the clinic’s litigation work, however, veterans with PTSD, TBI, and MST will have their bad paper automatically reviewed, pursuant to revised administrative procedures and following retraining of board staff. In separate class actions against the Army, the Navy/Marines, and most recently the Air Force, the clinic argued each branch’s discharge review boards were acting in an “arbitrary and capricious” manner to deny discharge upgrades.

Settlements with the branches mean tens of thousands of veterans will have another chance at life-changing benefits, and future veterans will benefit from the more generous standards now applied.

McCarthy, who worked on the class certification briefing in the case against the Army, says the experience was “energizing.”

“There was such a morally clear answer, and it was about how do we use the law to get to that point,” she said. “The clinic tends to take cases that are pretty innovative: often, there is no precedent directly on point. You just have to cobble it together and make a creative, good legal argument.”

The Monk brothers and their organization, the National Veterans Council for Legal Redress, were a major part of the discharge upgrade litigation: Conley Monk’s case led to new guidance from then Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel that veterans seeking discharge upgrades based on PTSD should be given “liberal consideration.” Conley Monk said such upgrades—which allow veterans to access their benefits—are the “most impactful” part of the clinic’s work.

Garry Monk agrees.

“That was the cornerstone of everything,” he said. Injuries like PTSD “are the invisibles. And now they are being acknowledged.”

Brandon Baum-Zepeda ’23 argued the motion for preliminary approval of the settlement with the Navy.

“It was really important to get any kind of relief to people as quickly as possible,” he said. “The material benefits are no doubt extremely important, but there is an enormous dignitary benefit as well.”

For people with bad paper, “it’s hard for them to feel proud of their service,” he added.

Class actions “make a huge difference” for veterans who need help, Markowitz said.

“There are a lot of benefits on the table for veterans,” she said. “But it’s really hard for an individual veteran without representation to go up against this huge government bureaucracy.”

United in Their Advocacy

The class action is an efficient procedural mechanism, as Davis acknowledged in the CAVC’s 2018 ruling: It saves judicial resources by combining many individual claims into one lawsuit. But, for veterans, the strategy also allows them to fight as a unit, as they were trained to do in the service.

Conley Monk’s discharge was upgraded; he now receives the benefits to which he is entitled. But he hasn’t stopped helping others.

“Knowing that vets are still having problems and still need help, that keeps me in the fight,” he said. “We have been in that fight, and we’ll continue to be in that fight.”

Brooks, whose father was in the Army, agreed.

“I come from a military family,” she said. “We’re very much taught that you live your life not just for yourself but for those around you. That ethos really carries through and that’s what the class action and collective work enable. That’s been most of our clients’ orientation.”

The clinic has helped veterans unite around a common cause in another context too. When a client complained to Wishnie about poor treatment of National Guard members when they are mobilized to assist a state or federal effort, Wishnie began to wonder about whether labor union protections could be extended to the servicemembers. Wishnie assigned student Josh Lefkow ’23, together with Jesse Tripathi ’21, to research whether a 1978 law making it a federal felony to organize a military union applied to National Guard members activated by their state governments.

Lefkow argued that the law would not apply in that context, but just to be sure, the clinic filed a pre-enforcement declaratory judgment action on behalf of several Connecticut state employee unions interested in organizing National Guard members if that were not a crime. Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Justice agreed with the clinic that the law does not apply to guard members when working in a state capacity, and the case settled. Since then, in part because of the clinic’s efforts, National Guard members ordered by the Texas governor to patrol the southern border have begun to unionize, joining the Texas State Employees Union.

Wishnie said students in the clinic follow the lead of their clients and strive to match their clients’ own courage and creativity with innovative and careful lawyering.

“There’s always something to be done,” Wishnie said. “It might be modest, it might take longer than it should, but there’s always some way to help.”

They have a choice of what to focus on in law school. They choose to be in this realm of helping veterans. Their authenticity comes through.”

—Garry Monk

Students who sign up for the clinic commit to working with veterans for one semester. But they can stay involved for as long as they like. Many students sign up as soon as they are able — in the spring of their 1L year — and continue for the remainder of their time in law school.

The Monk brothers said the students’ commitment is clear.

“They have a choice of what to focus on in law school,” Garry Monk said. “They choose to be in this realm of helping veterans. Their authenticity comes through.”

Petkun, now an associate professor at Duke Law, said he was “hooked immediately.”

“I knew from my first semester I was never going to stop,” he said. “The interactions with real-world clients, seeing the good that law can do, that appealed to me.”

Brooks, who returned to the clinic as a fellow after working on veterans’ issues for the New York Legal Assistance Group, agreed.

“The clinic was the center of my time in law school,” Brooks said. “I was delighted at the chance to jump back in and guide the next generation of students in the vets’ clinic.”