Q&A: LEAP Grant Recipient Sandra Amezcua Rocha

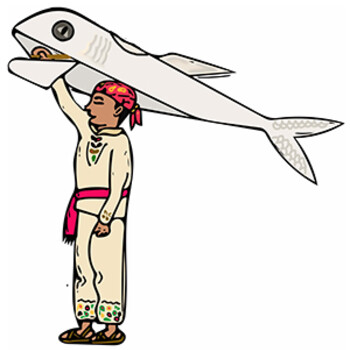

Sandra Rocha YC ’23 is a Law, Ethics & Animals Program4 (LEAP) student grant5 recipient and an environmental studies major at Yale College. Last winter, she traveled to Michoacán, Mexico to interview residents around Lake Pátzcuaro about how the indigenous P'urhépecha community contributes to conservation in the region. She also created a guide6 to P'urhépecha knowledge about species around the lake. A P'urhépecha translation of the guide is forthcoming.

LEAP Program Fellow Noah Macey spoke with Rocha about her work. An transcript, edited for clarity, follows.

How would you describe your project? What was it like to work in Michoacán?

The project focused on community relationships with Lake Pátzcuaro, its animals, and the ecosystem in general. Over the course of the project, I learned a lot about what these relationships actually look like and how they've been changing through generations. Among the people who I talked with, there were big age gaps. They spanned from 94-year-olds to, say, late teens.

The huge age gap meant that residents had different thoughts about what these animals were and what the lake means. The project was a lot of getting to know the land through the people, understanding the shifts that are happening and how people are reacting to them, and also how they’re unable to react or respond.

What was your day-to-day life like in Lake Pátzcuaro?

Pátzcuaro is my family home, so I would get outside my grandparents’ house to talk to strangers, meet people, and place myself in the community outside of my family. A lot of the way that the community works there is like, “Oh, who are you related to? Where are you coming from?” — that type of thing. Once those barriers are broken, it’s more individual, people can ask “Oh, who are you? What do you like?” and things like that.

So, day to day, there was a lot of going up to neighbors, knocking on doors, and having people tell me, “Oh, you should go knock on so-and-so’s door, they live around this area. Tell them I sent you.” It was a lot of tracing people. There were also lake visits to understand the state of the land. When I would talk to people, they’d tell me what the lake looks like, how to find animals, what time of day to find them, where to search, and all of those things — but then, when I actually went and looked for these animals and plants myself, I had to relearn everything.

That was most of it: interviewing people, out-of-the-blue a lot of the time, or navigating the lake and its surroundings.

What are some of the types of stories you were able to record?

The stories focused on animals around the lake, food, and hunting. And I expected that because I know that we eat a lot of food from the lake — I mean, we’re a fishing community, so our relationship with the lake and the fish comes back to us through stories. But there were other themes, too — I’d ask questions like, “What do you know about the achoque in the lake?” and they’d respond with recipes or healing practices using achoque. It was interesting to get those responses. I didn’t know about any of the healing practices, and I also got different takes on how people ate or fished or hunted or farmed these animals. Parts of the responses, like for the deer, would describe ceremonies and festivals that celebrate the animal and bring about a good hunting season. There were lots of cultural practices, beyond recipes, that I didn’t know about.

Has environmental damage made these animals scarcer or made these cultural practices harder to do?

Yes. One big difference in who had access to this knowledge about the achoque, or the deer, or other practices, was age. Older people knew so much more about it — and the way they’d describe the lake, you’d get the sense that the salamander population was always booming. Then I’d talk to people in their teens who’d say “Yeah, I’ve never seen one,” or “I’ve heard about them, but I’ve never had the chance to fish or hunt for [whichever animal].”

The stories I grew up listening to about the lake mentioned how close the lake is to the pueblo. Back in the day, the lake was about a 30- or 40-minute walk from town. Now it’s a two-hour walk because the water level is so much lower. And people can’t wash or bathe in the lake anymore because, first, it’s inconvenient to walk all the way over there, and also it’s very dirty now. When I talked to the elders though, they’d say, “Oh yeah, it was so clear I used to drink from the lake.”

Were the interviews you conducted mostly in Spanish or P'urhépecha?

I gave people the option of speaking in either because I did record everything. After that, depending on what they’d spoken, I worked with a translator a bit. So language wasn’t a problem. I definitely learned a lot more about P'urhépecha and P'urhépecha words that related to the animals and the lake. It was really nice because towards the end of the project I was recognizing more words in writing — for the most part, P'urhépecha is spoken, and very few people know how to write it. In general, older people would speak in P'urhépecha or a mix of that and Spanish, and people 30 and younger would prefer Spanish.

Could you describe what you’re doing with the guide you’ve created?

I wanted to create a living document that people would be able to interact with and provide feedback on, so that they could share stories of their own. But it was hard to come up with the easiest way to do that and reach people not only from Pátzcuaro, but also people like me, who are from there but who don’t live there. Reaching people has become a big focus.

We’ve uploaded the document6 to Google Drive and it’s been shared and circulated with the group I was working with, Jardin Etnobiologo de Santa Fe de la Laguna. One of the professors there, Dr. Bernal, and I have been in communication about the best way to circulate the document. But the people I talked to have also been given the document and communities in other parts of Pátzcuaro are spreading it. I’ve been working with a lot of P'urhépecha diaspora across Mexico, the U.S., and even Canada on social media platforms, trying to speak with them and connect them online, so that we can circulate the guide. I’ve met a lot of new folks through it. It feels very early in the process now, but it’s a great community.

How do you expect to continue doing this sort of work?

Before doing this project, I wasn’t sure of what path in environmental science I wanted to take. Now that I’ve started focusing on this, I have become more interested in how animals respond to and behave in changing environments, and that’s narrowed down a lot of my research focus. I’m working on a proposal for a research project looking at the animal behavior and conservation of achoque, the endemic salamander in Pátzcuaro that’s very culturally and ecologically important.

The Law, Ethics & Animals Program (LEAP) Student Grant Program seeks to support Yale University student-led research and creative projects during the academic year and the summer, focused on advancing understanding of, drawing attention to, and/or developing strategies to address the urgent threats facing non-human animals.