Tsai Center Visiting Scholar Spurs New Research to Support China’s Queer Families

When Yanhui Peng began pushing for LGBTQ equality in China through high-profile litigation in 2014, he never thought his advocacy would lead to direct engagement with national-level policymakers. Yet, when Peng started helping a lesbian woman, “Didi,” fight for custody of her children4 in 2019, that is exactly what happened.

That year, Didi’s same-sex partner left her and started denying her access to their two children, whom they had through assisted reproductive technology while living temporarily in California. With the assistance of a lawyer and Peng, Didi entered uncharted legal waters and sued for shared custody of her kids in a court in her ex-partner’s Zhejiang hometown.

“Chinese law does not consider the possibility that a child can have two mothers, but we believe recognizing both Didi and her ex-partner as mothers would be best for the children, Peng explained. “Ruling that one of them is a stranger to their own children would be tragic.”

Peng noted that China ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states that children’s best interests “shall be a primary consideration” in all actions concerning them.

To ensure Didi’s plight would not be ignored, Peng reached out to reporters, generating coverage of the story5 that quickly received hundreds of millions of views online. He then received an unexpected invitation.

“Out of the blue, a national conference of family law policymakers and scholars asked me to present about the case,” Peng recalled. “This was just what we had hoped for — that the case would make decisionmakers aware of China’s fast-growing number of queer families and the hardships they faced.”

The surprises did not stop there. After Peng’s conference presentation, several attendees approached him to express sympathy for Didi, but they also trepidatiously peppered him with questions. Were there really that many queer families in China? Did they all face challenges? Would having queer parents negatively affect a child’s development?

“Although I could point to research from abroad to try to answer these questions and allay their fears, there was precious little China-specific research I realized if we were going to make progress on this issue, we needed to change that,” Peng said.

But Peng soon found that scholars in China felt it was too risky to take the lead on researching this sensitive topic.

To brainstorm about how to fill the research gap, Peng reached out to Darius Longarino, a Senior Fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center who is a leading expert on LGBTQ rights in China.

“We discussed how legal recognition of queer families developed in other countries, which scholars in China wanted to know more about,” Longarino said.

Peng and Longarino also began identifying social scientists outside of China who could help Peng respond to policymakers’ questions.

“The more we talked, the clearer it became that there were a lot of people and resources at Yale and other U.S. universities that could help Peng develop his strategy further,” Longarino said.

In January 2022, Peng came to the Paul Tsai China Center as a Visiting Scholar.6

After arriving at Yale, Peng began researching how determining parentage, especially in the absence of marriage or a biological connection, evolved in the United States. He also dove into what role social science played in convincing courts and policymakers to protect the rights of queer parents.

Peng engaged in conversations with experts like Yale’s Anne Urowsky Professor of Law, Douglas NeJaime, the primary drafter of the Connecticut Parentage Act7; American University Washington College of Law Professor Nancy Polikoff, who authored Beyond (Straight and Gay) Marriage: Valuing All Families under the Law; and Wake Forest Law Professor Marie-Amélie George (Yale GAS ’18), the author of “The Custody Crucible: The Development of Scientific Authority About Gay and Lesbian Parents.” A team of student researchers from the Yale Law School Lowenstein Human Rights Project — Jack Baisley ’25, Suzanne Castillo YC ’23, Yang Shao ’25, and Andrew Wu YC ‘25 — also contributed memos to Peng on the development of determining parentage under California law and how U.S. courts have engaged with social science research in custody and marriage equality litigation.

“My time at Yale opened my eyes to how to broaden and diversify the law’s approach to determining parentage,” Peng said. “Advocates in China, including myself, often say that ‘love makes a family,’ and now we have legal frameworks that we can propose to put this into practice.”

“My time at Yale opened my eyes to how to broaden and diversify the law’s approach to determining parentage. Advocates in China, including myself, often say that ‘love makes a family,’ and now we have legal frameworks that we can propose to put this into practice.” —Yanhui Peng

Peng then turned back to the question of how to conduct research in China that would help convince policymakers there to provide legal protections to queer families. In October 2022, he and the Paul Tsai China Center invited an interdisciplinary group of scholars and advocates to participate in a workshop at Yale Law School, “Queer Parenting in China: Synthesizing Research and Advocacy.”

At the workshop, queer parents in China shared over videoconference their experiences and the challenges they have encountered. Zhijun Hu, the founder of China’s Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) and a Tsai Center Visiting Scholar attended the event in person. Hu shared that more and more queer parents were seeking advice from PFLAG about navigating myriad issues like how to introduce themselves to their child’s teacher or how to explain to their child why all school textbooks only refer to heterosexual parents.

Peng noted that in addition to Didi, many queer parents have confronted legal challenges. For example, in another case in which Peng was involved, a gay man’s partner was killed in a car accident. The deceased partner’s father then tried to claim custody8 over one of the couple’s children because the surviving partner had no biological connection to that child.

The workshop also covered the push for policy changes. A former Chinese lawmaker provided insight into how research and high-profile cases can influence the policymaking process. This speaker encouraged participants to pursue research that would help officials better understand queer families — and noted that the road to change would be long.

Workshop participants then discussed practical questions for research design and implementation, such as how advocates and scholars — who have different pressures and incentives — can collaborate to each other’s benefit. They continued by talking about what first steps should be taken given the lack of previous research and the political sensitivity of the topic in China; how research and advocacy could include all forms of diverse families to create a larger coalition of groups; and practical issues like how to secure funding support.

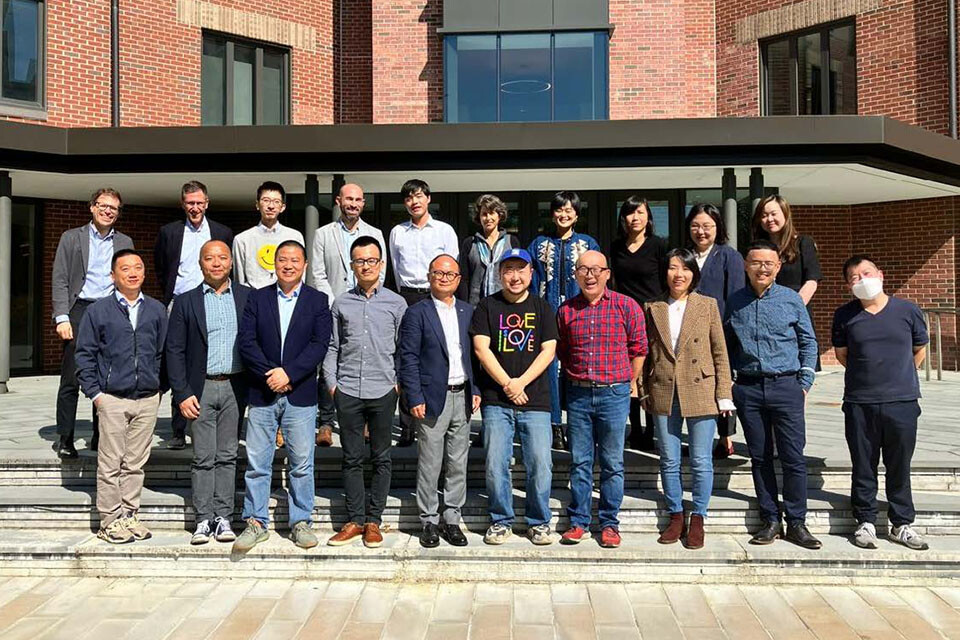

The attendees: in top row (left to right): Darius Longarino (Tsai Center Senior Fellow), Douglas NeJaime (Anne Urowsky Professor of Law, Yale Law School), Christopher Kakeung Wong (Master in Public Policy in Global Affairs, Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs), Ari Shaw (Director of International Programs, UCLA School of Law Williams Institute), Haoming Song (Ph.D. candidate, Brown University), Sara Friedman (Professor, University of Indiana), Di Wang (Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology, University of Wisconsin−Madison), Ke Li (Assistant Professor, John Jay College of Criminal Justice), Yun Zhou (Assistant Professor, University of Michigan), Krystal Wang (Ph.D. student, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health).

Attendees continued, bottom row (left to right): Yanhui Peng (Founder of LGBT Rights Advocacy China and Visiting Scholar, Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center), Wei Wei (Professor, East China Normal University), Zhijun Hu (Founder of China’s Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays and Visiting Scholar, Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center), Changhao Wei (Fellow, Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center), Dan Zhou (former Visiting Scholar, Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center), Guangchen Yang (Master’s Student, Mahidol University), Geoff Chin (International Project Manager, Los Angeles LGBT Center), Shufang Sun (Assistant Professor, Brown University), Suisui Wang (PhD Candidate, University of Indiana), Yiu-Tung Suen (Associate Professor, Chinese University of Hong Kong).

Workshop participant Professor Ke Li, a faculty member at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and author of Marriage Unbound: State Law, Power, and Inequality in Contemporary China9, said that the workshop “offered an invaluable opportunity to think hard about how to attune to scholarship to the needs of those seeking progressive changes in Chinese society.”

This connection between scholars and activists is important to Peng.

“Many activists in China are skeptical about the value of cooperating with scholars,” Peng explains. “They wonder, ‘Are we just being researched for a publication?’ After this workshop, I am much more confident that we can work together to create something that can have an impact on policymaking in China.”

Workshop attendees created a listserv to facilitate staying in touch and generating future projects together. Brown University School of Public Health Professor Shufang Sun, who has worked with scholars at Yale on developing LGBTQ-affirming mental health practices in China, has already begun collaborating with Peng on a project to conduct interviews of queer parents in China to better understand their daily lives.

“I was very inspired and energized by the workshop and I hope our research can serve as a tool to uncover barriers and facilitators to the reproductive health of LGBTQ+ people and the healthy development of children of queer parents in China,” Sun said.

Peng recognizes that research alone cannot bring about the change he seeks. When presenting at the Council on Foreign Relations, the Brookings Institution, and various law schools, he has emphasized the importance of public education in China. Without a shift in public opinion, changes in the law will not be possible.

That is why he thinks queer parents like Didi — whose case remains pending — play a critical role in moving the needle.

“Ideas like ‘rights’ and ‘equality’ are extremely important but can oftentimes sound too abstract to the public. On the other hand, ‘family’ and ‘love’ are things that everyone can relate to from their personal lives,” Peng said. “Mothers like Didi can change people’s hearts.”

Founded by Professor Paul Gewirtz in 1999 as the China Law Center, the Paul Tsai China Center10 is the primary home for activities related to China at Yale Law School. The Center is a unique institution dedicated to helping advance China’s legal reforms, contributing to the development of U.S.–China relations, and increasing understanding of China in the United States.