Working for Justice

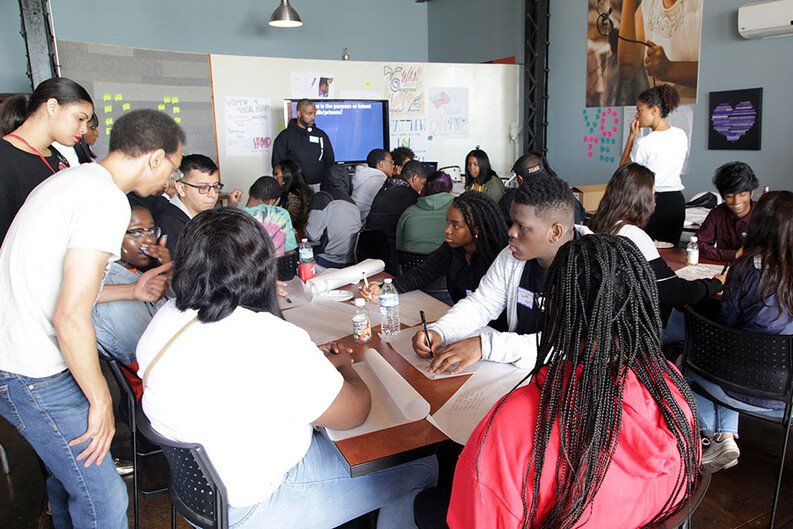

In 2018, not long after Amanda Alexander ’13 founded the Detroit Justice Center, an organization that seeks to transform the justice system, create economic opportunities, and promote equitable cities, she brought together young people from around Detroit and asked them to imagine what they would do with half a billion dollars — the amount of money their county had set aside to build new adult and juvenile correctional facilities.

The Restorative Justice Youth Design Summit was part of what Alexander calls “freedom dreams,” a term she borrows from the book of the same name by historian Robin D.G. Kelley. The idea is that, rather than just react to the bad things that can happen to their clients — losing a home, a driver’s license, or custody of a child — attorneys should proactively help their clients make good things happen. At the Detroit Justice Center, such work has facilitated the creation of urban farms, community land trusts, and cooperative businesses, among other projects.

“Those are freedom dreams,” Alexander says. “Our work as attorneys is really to listen to that and nurture that and support that.”

“I recognized that so much of the conversation was about what we were tearing down. There needed to be more room to talk about what we were building up.”

— Amanda Alexander ’13

Alexander decided to study law in part to learn how to better cultivate such dreams. The racial justice lawyer found what she needed at Yale Law School. So did Havi Mirell ’16, a federal prosecutor. And Reginald Dwayne Betts ’16, a poet who is launching a literacy program for people who are incarcerated. Also, Allison Frankel ’17, the Aryeh Neier Fellow at Human Rights Watch and the ACLU; Corey Guilmette ’16, a senior attorney at the Public Defender Association in Seattle; and Rachel Shur ’17, a public defender in New Orleans.

Collectively, these graduates work both in and outside a criminal justice system that people across the political spectrum agree needs to change. Yet they are all, in their own ways, working for justice. And the fact that they each credit Yale Law School with helping shape their thinking about and approach to that work is a testament to the breadth of the Law School’s criminal law and social justice curriculum.

In addition to their degrees from Yale Law School, these six attorneys share something else in common: their time on campus and early careers have been marked by high-profile incidents of police and racial violence and sustained periods of public protest denouncing such violence as the result of centuries of systemic racism. Before Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, there were Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner, all killed when these alums were students.

As Alexander points out, each death was “awful, but one in a very long line.”

“It was impossible for those cases not to have an impact on any person in the United States, let alone someone in law school studying the criminal justice system,” says Mirell, who works in the general crimes section of the Central District of California’s U.S. Attorney’s Office.

Paving the Path to Justice

Yale Law School offers students myriad opportunities to engage with the criminal justice system. It has two well-established centers that focus exclusively on criminal justice issues: The Justice Collaboratory, led by Professors Tracey Meares and Tom Tyler, and the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law, led by Professor Judith Resnik. The Justice Collaboratory posits that reforms can only come if there is increased trust and cooperation between individuals and the state. This year, the Center launched a new policing clinic and began a partnership with the Yale School of Medicine that brings together students and faculty to examine criminal justice at the intersection of the law and medicine. The Liman Center has been at the forefront of criminal justice work for decades, promoting access to justice and fair treatment through research, teaching, fellowships, and colloquia. In the classroom, criminal law is discussed, analyzed, and critiqued each semester through a wide variety of innovative classes, including Professor James Forman Jr.’s ’92 Inside Out and Access to Law School courses. Later this year, Forman will also launch the Center for Law and Racial Justice at Yale.

There are also many relevant clinical offerings, including: the Samuel Jacobs Criminal Justice Clinic, led by Clinical Professor Fiona Doherty ’99; the Prosecution Externship, led by Professor Kate Stith; the Challenging Mass Incarceration Clinic, led by Clinical Associate Professor Miriam Gohara; and The Criminal Justice Advocacy Clinic, led by Clinical Professor Marisol Orihuela ’08 and Gohara. The Strategic Advocacy Clinic, led by Professor Issa Kohler-Hausmann ’08, also launched last fall.

“It’s a system that is doing very little to help people and in many places is making it harder.”

— Allison Frankel ’17

As a student in the Liman Center, Alexander created the Women, Incarceration, and Family Law Clinic Project to help women who were incarcerated understand their rights in the context of maintaining custody of their children. That project led, after graduation, to a Soros Justice Fellowship that allowed her to launch a similar organization in her home state of Michigan, which, in turn, paved the way for the Detroit Justice Center.

Guilmette and Mirell also participated in the Liman Center’s work, researching how many people in the United States had been in solitary confinement and for how long, under the direction of Professor Judith Resnik as part of the center’s annual Time-in-Cell report. The research included sitdown meetings with correctional administrators.

“I was really surprised to hear they shared the same goals we did,” Guilmette says. “That taught me a lot about how to bridge divides and build unlikely allies.”

Betts, Frankel, and Shur all took, among other offerings, Doherty’s Samuel Jacobs Criminal Justice Clinic, through which Shur and Betts worked on a study of parole revocation that led to several reforms in Connecticut.

“Fiona was my first mentor in the field of public defense,” Shur says. “She tied in individual representation with how you can leverage insight and institutional power to get the ear of officials who have the ability to change a system.”

Betts, who is a Ph.D. candidate at Yale Law School, says part of the value of being on campus is the opportunity to connect and collaborate with highly motivated classmates and faculty.

“There are so many chances to meet and work with people who have the potential to have a real, transformative impact,” he says.

Mirell agrees, pointing to a class she took with Professor Kate Stith, a former federal prosecutor, as particularly influential.

“No one at Yale takes things for what they are,” she says. “Just because the system has always worked this way doesn’t mean it needs to. Yale really shifted that narrative. It makes you ask: Why is it? What could it be? And how?”

Shared Goals

It can be hard to remember in a time of increasing political polarization, but there is bipartisan and widespread support for criminal justice reform in this country. In 2018, every Democratic and all but 12 Republican Senators voted in favor of the First Step Act, which, among other things, was designed to reduce the U.S. prison population, eliminate sentencing disparities, reduce recidivism, and expand early-release programs. After the death of George Floyd last year, Republicans and Democrats in Congress each proposed police reform bills although they ultimately could not reach an agreement on either.

In this climate, these alums have taken their commitment to a fairer criminal justice system in different directions. Shur, Mirell, and Guilmette each worked for a year as Liman Fellows— Shur in the Orleans Public Defenders office, where she focused on the disparate impact of fines and fees on indigent people and remains a staff attorney; Mirell in the executive branch of the Rhode Island state government, where she worked on battling opioid addiction among incarcerated people and gun safety issues before ultimately joining the U.S. Department of Justice; and Guilmette at the Public Defender Association in Seattle, where he continues to work to improve the public review process for deaths involving law enforcement.

“What would it mean if we put millions of books in prison? If we transformed the space and out of the rubble came the wings that books grant people and the freedom you get from books?”

— Dwayne Betts ’16

Earlier this year, Betts created the Million Book Project, which will distribute curated 500-book collections to medium and maximum-security prisons and juvenile detention centers. Housed at Yale Law School’s Justice Collaboratory, the project was recently awarded a $5.25 million grant from the Mellon Foundation and seeks to enhance the role of literature in the lives of people who are incarcerated.

Betts, who has written extensively about his own time in prison and won a 2020 American Book Award for his book Felon: Poems, says he “stole the idea” from the prison system, which houses millions of people.

“What would it mean if we put millions of books in prison?” he asks. “If we transformed the space and out of the rubble came the wings that books grant people and the freedom you get from books?”

Frankel is also focused on the conditions that make freedom possible. At Human Rights Watch, she researched and wrote Revoked: How Probation and Parole Feed Mass Incarceration in the United States, a 225-page report published in July that documents how parole and probation facilitate a return to confinement, rather than life outside it.

According to her report, one out of every 55 adults in the United States is on probation or parole, and, although Black people make up only 13 percent of the population, they account for 30 percent of people under supervision. Moreover, nearly half of people entering state prisons are sent there for supervision violations, and most of them were not convicted of new offenses; instead, they are punished for breaking the rules of their probation or parole.

“It’s a system that is doing very little to help people and in many places is making it harder,” Frankel says.

Frankel makes several recommendations, including divesting — or diverting — resources away from supervision and investing those additional resources in jobs, housing, education, and voluntary, community-based mental health and substance use treatments and services.

“The most exciting thing — if I can be excited about anything in the world right now — are these calls to divest funding away from policing and incarceration and into communities,” she says. “That’s something abolitionists and activists have been saying for decades and decades, and it’s increasingly mainstream.”

What could be done with resources that are diverted away from punitive criminal justice policies? Helping people answer that question is one reason Alexander created the Detroit Justice Center—that’s what “freedom dreams” are all about.

“I recognized that so much of the conversation was about what we were tearing down,” Alexander explains. “There needed to be more room to talk about what we were building up.”

At the Restorative Justice Youth Design Summit she hosted in 2018, when dozens of young people working in teams were asked to come up with alternative ways to spend the $533 million that had been set aside for correctional facilities in their community, they didn’t have any trouble. The students, ranging in age from 13 to 18, were “full of ideas,” Alexander says. They rattled off plans for community centers, schools, libraries, affordable housing, transit projects, and mental health services.

It was a start.

“We said, ‘Keep going,’” Alexander recalls. “‘You could do all this and more.”