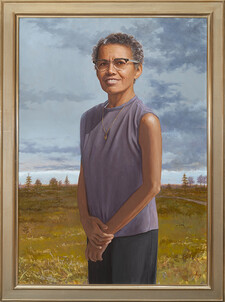

Historical Profile: Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray ’65 JSD

A true trailblazer, Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray ’65 JSD was a scholar, activist, writer, and Episcopal priest who was an important yet often overlooked figure in the civil and women’s rights movements. Murray's life was spent fighting the racial and gender barriers that were constantly working against them, and their ideas had a significant impact on prominent changemakers including Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Murray made history at Yale when they became the first Black person to graduate from the Law School with a J.S.D. Murray was later awarded an honorary degree from the Divinity School in 1979 after becoming the first Black female-bodied Episcopal priest.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, as Anna Pauline in 1910, Murray was raised by family members in Durham, North Carolina, after their mother’s death in 1914. From a young age, Murray grappled with the complexities of their racial identity. Their lineage included enslaved African and Native Americans as well as white slaveholders. The house Murray grew up in belonged to their maternal grandmother, who was born a slave and fathered by the son of her mother’s enslaver, and maternal grandfather, who was a Union soldier in the Civil War and later established schools for freed slaves. Painfully aware of the disparities between Black and white people of their time, Murray’s experience growing up in the segregated South fueled their future work as a civil rights activist.

After graduating from high school at only 15 years old — and at the top of their class — Murray was eager to start a new life in New York City. Murray couldn’t apply to Columbia University, their top-choice for college, due to their assigned gender. Unable to afford the tuition for Columbia’s women’s college, Barnard, Murray enrolled in Hunter College where they graduated in 1933 with a degree in English literature.

The 1930s was an era marked by struggle for Murray. The Great Depression made financing their education nearly impossible, and job prospects were incredibly slim. Murray developed an interest in workers’ rights and spent time working for the Works Progress Administration’s Workers Education Project and the National Urban League. It was also during this time when Murray would begin to struggle with gender identity and go by the androgynous nickname of “Pauli.” Murray spent the rest of their life feeling out of place in their own body and in later years were denied gender-affirming medical care, specifically hormone therapy.

In 1938, Murray decided to return home and applied to a graduate program in sociology at the University of North Carolina. Despite their deep familial ties to the school — which included two alumni, a board of trustees member, and a scholarship founder — and a fortuitous Supreme Court ruling that should have allowed admittance, Murray's application was denied on the basis of race.

Murray continued to face racial discrimination in the South. While traveling by bus from New York to North Carolina in 1940, Murray and a friend were arrested after refusing to sit in the bus’s designated — and defective — seats for Black passengers. The event — which took place 15 years before Rosa Parks’ arrest led to the Montgomery bus boycott — caught the attention of the NAACP, which saw it as an opportunity to combat segregation. However, in the end Murray was merely charged with disorderly conduct and thus never saw their day in court.

A few months later, Murray was called upon by the Workers Defense League to raise funds for Odell Waller, a Virginia sharecropper who had been sentenced to death for killing his landlord in what he claimed was self-defense. The case was a turning point in Murray’s career. Not only did it solidify their passion for ending segregation, but it also connected them with two mentors who opened the door to legal education. While fundraising in Virginia, Murray met Leon Ransom, a law professor at Howard University who encouraged Murray to enroll in the school and secured them a scholarship, and Thurgood Marshall, who wrote a recommendation letter. Though not yet written at the time, Marshall would later rely on Murray’s book States’ Laws on Race and Color while preparing for the Brown v. Board of Education case that defined his career and ultimately brought an end to segregation in the United States.

Murray started law school at Howard in the year following the arrest. They began to label themself as “Jane Crow,” a term they used to refer to the combined discrimination Black women experience. Murray would later write more about the intersectionality of racism and sexism in a George Washington Law Review article co-authored with Mary Eastwood titled, “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII.” Ruth Bader Ginsburg credited Murray in the amicus brief of Reed v. Reed for the influence their article had on the landmark case.

Murray graduated from Howard in 1944 at the top of the class — of which they were the only female-bodied person — and received the Rosenwald Fellowship for post-graduate academic pursuits. After being denied admission to Harvard Law School because of their assumed gender, Murray enrolled in an LL.M. degree program at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, where they graduated in 1945.

Following graduation from Berkeley, Murray made their way back to New York. In 1956, they landed a position as an associate at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton and Garrison, where they briefly overlapped with then-summer associate Ruth Bader Ginsburg. It was also at Paul, Weiss where Murray met their longtime romantic partner, Irene Barlow. Murray left the firm in 1960 to teach at a newly established law school in Ghana’s capital. Their tenure was short-lived due to the political instability in the country, and they moved back to the United States to enroll in Yale Law School’s J.S.D. program. While at Yale, Murray served on the President’s Commission on the Status of Women in the Kennedy administration and was part of the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Their dissertation was titled “Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy.” Murray became the first Black person to graduate from the J.S.D. program in 1965, and a year later joined Betty Friedan, a leader in the women’s movement, and several others, to form the National Organization for Women.

Murray eventually landed a faculty position at Brandeis University where they taught from 1968 to 1973 and was, fittingly, the first person to teach African American and women’s studies at the university. Despite their tenured position, Murray made the decision to leave Brandeis and enter the General Theological Seminary with the intention of becoming an Episcopal priest. The fact that women weren’t yet allowed to be ordained by the Episcopal Church didn’t stop them, and they completed their studies in December 1976. As fate would have it, the Church decided to change their policy just as Murray finished seminary school training and in 1977, became the first Black female-bodied person to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Murray marked the occasion with a visit to North Carolina where they performed their first Eucharist in the church their maternal grandmother was baptized in, with a Bible given to them by that grandmother. Two years later, the Yale Divinity School presented Murray with an honorary doctorate degree during Commencement in 1979.

Murray died of cancer in 1985. Two years after their death, Murray's autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was published. Murray’s legacy has been memorialized with the naming of Pauli Murray College, one of Yale’s residential colleges, and a special edition of the U.S. quarter set to be released in 2024. Their family home in North Carolina was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 2016. The Award of Merit, the Yale Law School Association’s highest honor, was given to Murray posthumously during Alumni Weekend 2022 and a portrait of Murray is on display at Yale Law School4.

In honor of the Law School’s bicentennial, the Lillian Goldman Law Library is holding a rare book exhibit during the spring 2024 term which will include Murray’s dissertation, “Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy” (1965), and an essay they wrote with Murray Kempton titled “All for Mr. Davis: The Story of Sharecropper Odell Waller,” published in The Rights of Man Are Worth Defending (1942).